|

Abstract:

Congenital anomalies of the gallbladder, such as

the bilobed gallbladder (vesica fellea

divisa), are rare clinical entities with

an estimated incidence of 1 in 4,000 live

births. These variations pose significant

intraoperative challenges, particularly when

compounded by a "frozen abdomen" from previous

surgical interventions. We report a unique case

of a 30-year-old male with a history of open

surgery for hepatic hydatid disease who

presented with recurrent right hypochondrium

pain and vomiting. Preoperative imaging

identified a large splenic hydatid cyst and

cholelithiasis. While the splenic cyst was

managed laparoscopically after insertion of the

first trocar via Palmer’s point to avoid

suspected adhesions, the gallbladder surgery

required conversion to an open approach due to

dense, matted adhesions at the gallbladder bed.

Intraoperatively, a rare vesica fellea

divisa (Boyden’s type) was discovered,

containing multiple calculi in both lobes but

draining into a single cystic duct. A total

cholecystectomy was successfully performed.

Histopathological examination confirmed a

splenic hydatid cyst and chronic cholecystitis

with no evidence of malignancy. The patient

remained asymptomatic and expressed high

satisfaction at his six-month follow-up. This

case underscores the rarity of splenic

hydatidosis and the critical need for surgical

flexibility and meticulous anatomical

delineation when encountering unexpected

congenital biliary anomalies in a re-operative

surgical field.

Key

Words: Bilobed gallbladder, Splenic

hydatid cyst, Boyden's classification, Frozen

abdomen, Cholecystectomy, Vesica fellea divisa.

|

|

Introduction

The

gallbladder is known for a wide range of

congenital anatomical variations, which often pose

significant challenges during surgical

interventions. Among these, the duplicated

gallbladder is an exceedingly rare anomaly with an

estimated incidence of approximately 1 in 4,000

live births [1, 2]. They are often asymptomatic

but can become clinically significant when

complicated by cholelithiasis or when they coexist

with other pathologies. Surgeons need to be aware

of this congenital abnormality due to its

association with anatomical variations of the

hepatic artery and cystic duct. There are two

classification systems for duplicated gallbladder,

namely Boyden's classification and Harlaftis

classification [3]. Boyden's classification is

more widely accepted due to its simplicity, and it

describes two main types:

- Vesica fellea divisa: wherein

there is a bilobed gallbladder draining into a

single cystic duct,

- Vesica fellea duplex: wherein

gallbladder is truly duplicated and draining

into separate cystic ducts. This type is

sub-classified into the “Y-shaped type” (two

cystic ducts uniting and then entering the

common bile duct), and the “H-shaped or ductular

type” (two cystic ducts entering separately into

the common bile duct).

Hydatid disease,

caused by Echinococcus species, remains

a significant public health concern in endemic

regions. While the liver is the most common site

of infection (70%), splenic hydatid cysts are

rare, accounting for only up to 5% of all cases

[4]. This rarity is attributed to the "filtering"

action of the liver and lungs, which act as the

first and second barriers to the systemic

circulation of embryos.

The simultaneous

clinical presentation of a symptomatic splenic

hydatid cyst and a congenital vesica fellea divisa

represents an exceptionally rare surgical

intersection. We herein present one such case to

highlight the diagnostic challenges and technical

nuances required to manage such concurrent

pathologies in the presence of a frozen abdomen.

Case Presentation

A 30-year-old male

presented with a one-year history of recurrent

vomiting and pain in the right hypochondrium

(RHC). His past medical history was significant

for an open surgical intervention for hepatic

hydatid disease performed three years prior.

Ultrasonography (USG) suggested the presence of a

splenic cyst and cholelithiasis. A subsequent

Computed Tomography (CT) scan confirmed a large

cystic lesion in the spleen, characteristic of a

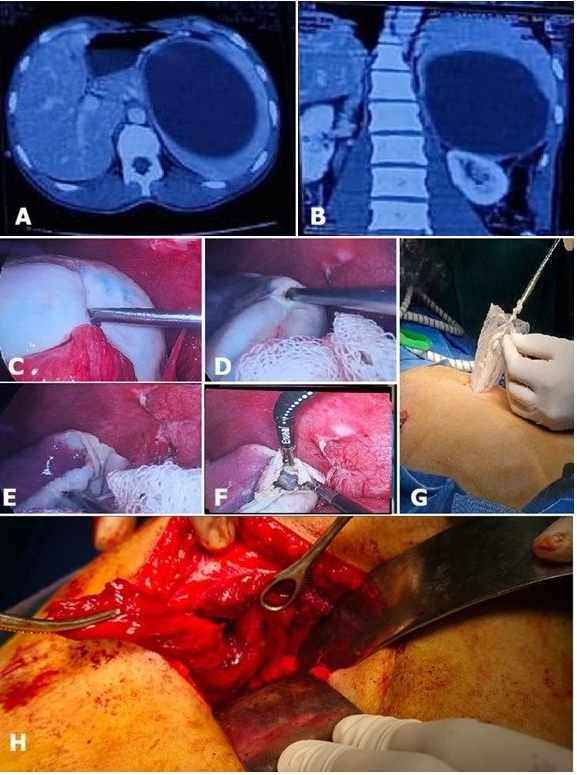

Gharbi Type 1 - hydatid cyst (Figure 1 A, B),

alongside a distended gallbladder containing

multiple calculi. The splenic cyst measured

approximately 12 x 10 x 9 cm with an estimated

volume of about 550 mL. Serological testing,

specifically Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

(ELISA) and Indirect Hemagglutination (IHA) for Echinococcus

antibodies, returned positive results, providing

immunological confirmation of hydatid disease.

The procedure began

with a diagnostic laparoscopy. To avoid suspected

dense adhesions from the previous hepatic surgery,

access was gained via Palmer’s point. The splenic

hydatid cyst was successfully managed using a

laparoscopic approach (Figure 1 C-G). However,

upon exploration of the right hypochondrium,

"frozen" anatomy was encountered. Dense, matted

adhesions involving the omentum, colon, stomach,

and duodenum were found at the gallbladder bed,

resulting from the previous open hepatic surgery.

Due to the inability to safely visualize Calot’s

triangle, the team converted to an open approach

via a right subcostal incision over the old scar.

Following extensive

adhesiolysis, a congenital anomaly was discovered:

a bilobed gallbladder (vesica fellea divisa). Both

lobes were filled with multiple calculi.

Meticulous dissection revealed that both lobes

drained into a single cystic duct and were

supplied by a single cystic artery (Figure 1 H). A

total cholecystectomy was successfully performed.

Histopathological

examination confirmed the diagnosis of a hydatid

cyst of the spleen and revealed features of

chronic cholecystitis in the gallbladder specimen,

with no evidence of malignancy in either lobe. The

patient's postoperative recovery was uneventful.

At the six-month follow-up, the patient reported

complete resolution of symptoms and expressed high

satisfaction with the surgical outcome.

|

| Figure

1: Radiological and Intraoperative

Findings. (A, B)

Axial and coronal sections of the abdominal

computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrating

a large, unilocular splenic hydatid cyst. (C–G)

Sequential intraoperative steps showing the

laparoscopic evacuation and management of

the splenic hydatid cyst. (H)

Intraoperative view after conversion to open

surgery, showing the two distinct lobes of

the bilobed gallbladder (vesica fellea

divisa) held with surgical

instruments for anatomical delineation. |

Discussion

The discovery of a

bilobed gallbladder intraoperatively is a rare

event that demands meticulous surgical technique

to ensure the "critical view of safety" and

prevent iatrogenic injury. Based on the Boyden

classification, our case fits the description of vesica

fellea divisa. In this subtype, the

gallbladder primordium divides during the 5th or

6th week of gestation, resulting in two lobes that

communicate through a single cystic duct [3].

In this patient, the

surgical complexity was significantly increased by

a prior open hepatic hydatid surgery. Previous

interventions for hydatid disease are often

associated with dense, "matted" adhesions

involving the omentum, stomach, and duodenum,

leading to what is clinically described as a

frozen abdomen [5]. While the splenic hydatid cyst

was successfully managed laparoscopically via

Palmer’s point to avoid adhesions, the gallbladder

pathology necessitated conversion to an open

approach. Literature suggests that conversion

rates are higher in patients with previous upper

abdominal surgeries due to the high risk of

visceral injury during laparoscopic dissection of

the Calot’s triangle [6].

The presence of

multiple gallbladders or lobes does not

necessarily increase the risk of cholelithiasis;

however, if stones are present, they usually

affect both lobes, as seen in our patient. It is

imperative for the surgeon to excise both lobes

entirely to prevent "stump cholecystitis" or

recurrent symptoms from a residual lobe [7].

This case highlights

the importance of maintaining a high index of

suspicion for anatomical variations even when

preoperative imaging is inconclusive. The

successful management of a rare splenic hydatid

cyst alongside a congenital biliary anomaly

underscores the need for surgical flexibility and

careful intraoperative anatomical delineation.

Conclusion

This case emphasizes

the necessity of surgical flexibility when

managing rare congenital and infective pathologies

in a re-operative field. The presence of a "frozen

abdomen" often necessitates a low threshold for

conversion from laparoscopy to an open approach to

ensure the safe visualization of anatomical

landmarks. Intraoperatively, the discovery of a vesica

fellea divisa demands meticulous dissection

to identify the single cystic duct and artery.

Ultimately, thorough intraoperative evaluation and

complete resection of all gallbladder lobes are

paramount to preventing recurrent symptoms and

ensuring successful surgical outcomes.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for the publication of this case report

and any accompanying images.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere

gratitude to the patient for his cooperation and

for providing consent to share this clinical

finding with the medical community.

References

- Kumar M, Adhikari D, Kumar V, Dharap S.

Bilobed gallbladder: a rare congenital anomaly.

BMJ Case Rep. 2018 Feb 11;2018:

bcr2017222783. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-222783.

- Pillay Y. Gallbladder duplication. Int J

Surg Case Rep 2015; 11:18–20.

10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.04.002

- Robele TK, Mulugeta S, Knfe G, Dagne D,

Shiferaw E. Duplicated gallbladder with stones:

Rare anomaly of the biliary system. Int J

Surg Case Rep. 2024 Sep; 122:110106. doi:

10.1016/j.ijscr.2024.110106.

- Rasheed K, Zargar SA, Telwani AA. Hydatid cyst

of spleen: a diagnostic challenge. N Am J

Med Sci. 2013 Jan;5(1):10-20. doi:

10.4103/1947-2714.106184.

- Gómez Pérez JM, García Fernández GA, Lizárraga

Castro JA, Gómez Pérez AP, López Castillo R,

Hernández Álvarez CR. A review for hostile and

frozen abdomen. Int J Med Sci Clin Res Stud.

2024;4(9):1652–1654.

doi:10.47191/ijmscrs/v4-i09-10.

- Abraham S, Nemeth T, Benko R, et al.

Evaluation of the conversion rate as it relates

to preoperative risk factors and surgeon

experience: a retrospective study of 4013

patients undergoing elective laparoscopic

cholecystectomy. BMC Surg. 2021;21:151.

doi:10.1186/s12893-021-01152-z.

- Gigot J, Van Beers B, Goncette L, Etienne J,

Collard A, Jadoul P, Therasse A, Otte JB,

Kestens P. Laparoscopic treatment of gallbladder

duplication. A plea for removal of both

gallbladders. Surg Endosc. 1997

May;11(5):479-82. doi: 10.1007/s004649900396.

|