|

Introduction

Ensuring

public access to quality healthcare services

relies on the fair distribution of health

resources such as healthcare professionals across

different geographical areas. The distribution of

health resources in a specific geographical area

greatly impacts people's access to healthcare [1].

Shreds of evidence indicate that a higher density

of healthcare professionals has a positive

correlation with health outcomes [2-3], healthcare

accessibility [4-6], and healthcare utilization

[7]. This underlines the significance of policies

that aim at increasing the supply of healthcare

professionals to improve health outcomes,

healthcare utilization, and healthcare equity.

Globally, ensuring fairness in distributing

healthcare resources is considered a major

challenge in the healthcare sector [8]. The

allocation of healthcare resources in countries

can be influenced by political factors that

frequently dictate resource allocation,

disregarding the populations' health needs in a

specific area [9]. The knowledge of the

distribution of healthcare professionals helps

determine if the distribution of the healthcare

professionals aligns with the population's health

needs. This will shed light on broader health

system challenges such as variations in the

quality of healthcare, disparities in healthcare

access, and informing strategies to improve health

services [10-16].

Health services in

the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) have

significantly improved in the last two decades,

with greater access to healthcare resources

nationwide. The Ministry of Health (MOH) is the

major provider with about 60% of all services, and

the remaining share is divided among other

government and private sectors [17-18]. Since the

early 1990s, the private sector, the main provider

of health services for expatriate workers played a

role in the enhancements of healthcare delivery

through employer-contributed health insurance.

With the improved health services, there has been

a substantial increase in the number of healthcare

professionals over the last few years. According

to the MOH’s statistical yearbook, there were

105,332 physicians, 23897 dentists, 200,558 nurses

and midwives, and 34,040 pharmacists in the

Kingdom in 2022 [19]. Between 2010 and 2022, the

Kingdom recorded a 95.8% increase in physicians

(including dentists), 54.5% in nurses and

midwives, and 128% in pharmacists. Even though the

ratio of physicians, nurses, and pharmacists per

10,000 people increased in 2022, it is still lower

than in other high-income countries [20].

Currently, the ratio of physicians per 10,000

people in the KSA (31) is lower compared to

Germany (45), the USA (36), the UK (32), and the

European Union (43). The number of 56 nurses and

midwives per 10,000 people in the KSA is much

lower compared to Germany (123), the USA (125),

the UK (92), and the average for the European

Union (77) [20]. However, the number of

pharmacists in the KSA (9.35 pharmacists per

10,000 people) is comparable with countries such

as the UK (9.06), the USA (9.6), and Australia

(9.3). [20]. In comparison to other Gulf

Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, the KSA has a

higher physician-to-population ratio, whereas

Qatar (72) and the United Arab Emirates (64) have

higher nurse-to-population ratios [20].

Saudi Vision 2030

aims to transform the healthcare system in Saudi

Arabia, with a significant focus on improving the

distribution and composition of healthcare

professionals [21]. The National Transformation

Program (NTP) 2020 places a strong emphasis on

achieving equal distribution of health resources

across all regions of the Kingdom [22]. The aim is

to create a more equitable healthcare system that

provides high-quality services to all citizens and

expatriates, regardless of their location within

the Kingdom. This approach aligns with the broader

goals of Saudi vision-2030 to improve the

population’s health and well-being [23]. Moreover,

the Saudi health system is significantly affected

by the rising number of non-communicable diseases

(NCDs) and the increasing aging population,

specifically concerning the distribution of

healthcare resources [24-25]. Additionally,

chronic illnesses such as heart diseases, cancers,

and diabetes, are becoming more prevalent due to

changing lifestyles and aging, leading to a

greater need for prolonged medical treatment and

subsequently higher demand for healthcare

professionals [24].

The need for

healthcare services and hence healthcare

professional requirements across regions vary

depending on morbidity and mortality patterns.

Moreover, the composition of morbidity and

mortality may differ by region. The regions with

lower population density may require a greater

health professionals-population ratio [13].

Therefore, achieving a balanced and equitable

distribution of healthcare resources according to

demographic and geographical aspects is a real

challenge in most countries [26]. Recent studies

conducted in various countries used techniques

like Gini coefficients and Theil index for

assessing the geographical inequalities in the

distribution of health resources including the

health workforce. A study in Iran used Gini

coefficient and Hirschman-Herfindahl index to

assess fairness in the distribution of healthcare

specialists [27]. Recent studies in China employed

the Gini coefficients and Theil index to assess

the geographical inequalities in the distribution

of health resources [28-30]. In the KSA, existing

studies show that resources are distributed fairly

at the national level, but there are noticeable

differences in the distribution of physicians,

nurses, and pharmacists between regions, with

urban areas typically having better access than

rural areas [17, 24]. Few studies conducted in the

KSA showed disparities in terms of healthcare

access, and resources. For instance, a study in

Riyadh showed that a significant proportion of the

population had to travel long distances to access

healthcare services [26]. A study by Hawsami and

Abouammoh (2022) highlighted inequalities in the

distribution of hospital beds in the private

sector [31]. Similarly, a study on the

distribution of primary healthcare centers in the

KSA highlighted a significant regional disparity

across various health regions [32]. However,

another study by Kattan and Alshareef (2022)

showed a relatively equitable distribution of

hospital beds across various regions [33]. This

study addresses a critical gap in the literature

by measuring inequalities in the distribution of

health professionals across health regions of the

KSA using the Gini coefficients and Lorenz Curves.

While other studies have used Gini coefficients

and Lorenz curves to measure healthcare inequality

globally, this research applies these metrics to

the unique healthcare landscape of the KSA,

offering country-specific insights. Moreover, in

the KSA no attempt has ever been made to assess

the current status of the distribution of

healthcare professionals across different health

regions.

Therefore, this

research addresses the research question “to what

extent do the 20 health regions in the KSA differ

in their availability and density of healthcare

professionals’. The research assesses the equity

in the distribution of healthcare professionals in

the health regions based on the recent data

published by the MOH. The study pinpoints the

deficiencies in the distribution of healthcare

professionals and identifies the health regions

that are not keeping pace with the overall

development of healthcare professionals in the

Kingdom. It also provides an estimate of

additional requirements for healthcare

professionals in regions based on global

standards. The specific benchmark threshold levels

for physicians, dentists, nurses, and pharmacists

to achieve the universal health coverage (UHC)

effective coverage index based on the Global

Burden of Disease Study 2019 was used. By

addressing these gaps, the study contributes

valuable country-specific data to inform targeted

interventions and policies aimed at improving

health equity in the KSA. It is also expected that

the findings of the study could aid in

implementing necessary policy interventions and

promoting discourse on healthcare equity and

resource allocation in the KSA.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

In this research, a

secondary data analysis was conducted to assess

the distribution of physicians, dentists, nurses

and midwives, and pharmacists across the 20 health

regions of the KSA in 2022. Data on the number of

physicians, dentists, nurses (including midwives),

pharmacists employed by the MOH and the private

sector, and demographic information for each

region were obtained from the statistical Yearbook

of the MOH, which is viewed as an authentic source

of information on health-related data in the KSA.

The MOH statical yearbook provides detailed

information on healthcare professionals of all

regions in the KSA as reported to the Ministry at

the end of each year. This study includes data on

MOH facilities and private health facilities

across 20 health regions. The analysis considered

the population of both Saudi citizens and

expatriates, across the health regions. The

estimates of the population for 2022 in the

regions were compiled from the MOH Statistical

Yearbook [19]. This is the mid-year population

estimate produced by the national statistical

agencies. In this research population estimate for

2022 was used to estimate the density of

healthcare professionals per 10,000 population in

20 regions [19]. This measure is regarded as a

standardized unit of measurement for comparing the

availability of healthcare professionals across

different regions with varying population sizes

[28]. It would also serve as a measure of the

healthcare services access in different regions in

the KSA.

Study tools

and data extraction

A spreadsheet was

created using Microsoft Excel 2016 to retrieve

data such as health region, year, population,

physicians, nurses, and pharmacists from the MOH

Statistical Yearbook. To evaluate the equity in

the allocation of healthcare professionals such as

physicians, dentists, nurses, and pharmacists

across 20 health regions, the Lorenz curve and

Gini coefficient were computed and visualized with

Excel, 2016. While the Lorenz curve is a graphical

tool that allows for comparing inequalities about

a state of perfect equality, the Gini coefficient

is a statistical measure utilized to evaluate

disparities in the distribution of resources in

society [34]. The Gini coefficient is the most

commonly used measure of inequality, making it

easily understood and comparable across different

studies and contexts. The Gini coefficient is

independent of the size of the economy and the

size of the population, making it suitable for

comparing regions with different population sizes.

This measure is more sensitive to changes around

the middle of the distribution than at the very

top and bottom, which can be useful for capturing

changes in the distribution of health

professionals [35].

In the Lorenz curve,

the x-axis shows the cumulative percentage of the

population, the y-axis depicts the total

percentage of healthcare professionals in the

regions. The graph displays a diagonal line to

represent perfect equality, with the Lorenz curve

typically situated beneath it. The Gini

coefficient is computed from the graph by

comparing the area below the diagonal line with

the curve to the total area under the line of

equality [34]. The interpretation of the different

Gini coefficient values is presented in Table 1.

|

Table 1: Interpretation of the Gini

coefficient values

|

|

Gini coefficient

|

Evaluation of equity

|

|

≤ 0.2

|

Perfect equality

|

|

> 0.2–0.3

|

Relative equality

|

|

> 0.3–0.4

|

Adequate equality

|

|

> 0.4–0.5

|

Large equality gap

|

|

> 0.5

|

Severe equality gap

|

In this research,

additional requirements for physicians, dentists,

nurses, and pharmacists in regions were estimated

based on a threshold level established based on

the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. For the

first time, Haakenstadsed et al (2022) calculated

healthcare professionals thresholds for

physicians, dentists, nurses and midwives, and

pharmacists using the universal health coverage

(UHC) effective coverage index [36]. These

thresholds are essential to reach target UHC

levels if countries efficiently utilize the

healthcare professionals for UHC. To achieve a

score of 80 on the UHC effective coverage index,

for every 10,000 people, a minimum of 20.7

physicians, 8.2 dentists, 70.6 nurses and

midwives, and 9.4 pharmaceutical personnel would

be required.

Results

Table 2 shows the

overall availability of physicians, dentists,

nurses and midwives, and pharmacists in The KSA

during the last five years (2018-2022). The

country, which houses about 32.2 million people,

has 32.74 physicians, 7.43 dentists, 62.33 nurses

and midwives, and 10.58 pharmacists per 10,0000

people in 2022. This number only reflects the

overall healthcare professionals capacity in the

Kingdom, but hides significant regional

differences in the distribution of various

categories of health professionals.

|

Table 2: Five-year availability of

healthcare professionals in the KSA from

2018 to 2022*

|

|

Year

|

Population

|

Category

|

Number

|

Per 10,000 people

|

|

2018

|

29,647,968

|

Physicians

|

88023

|

29.68

|

|

Dentists

|

16752

|

5.65

|

|

Nurses and Midwives

|

184565

|

62.25

|

|

Pharmacists

|

29125

|

9.82

|

|

2019

|

30,196,281

|

Physicians

|

94335

|

31.24

|

|

Dentists

|

18811

|

6.23

|

|

Nurses and Midwives

|

199013

|

65.90

|

|

Pharmacists

|

31872

|

10.55

|

|

2020

|

30,063,799

|

Physicians

|

95336

|

31.71

|

|

Dentists

|

19622

|

6.53

|

|

Nurses and Midwives

|

196701

|

65.43

|

|

Pharmacists

|

27529

|

9.16

|

|

2021

|

31,552,510

|

Physicians

|

99617

|

38.78

|

|

Dentists

|

22739

|

7.21

|

|

Nurses and Midwives

|

201489

|

63.85

|

|

Pharmacists

|

30840

|

9.77

|

|

2022

|

32,175,224

|

Physicians

|

105332

|

32.74

|

|

Dentists

|

23897

|

7.43

|

|

Nurses and Midwives

|

200558

|

62.33

|

|

Pharmacists

|

34040

|

10.58

|

Source: Compiled

from the Annual Statistical Yearbook, MOH,

KSA,2022

Note: * This data

includes physicians, dentists, nurses and

midwives, and pharmacists employed in the MOH

health facilities, other government

ministries/agencies, and the private sector

Table 3 provides

region-wise distribution of physicians, dentists,

nurses and midwives, and pharmacists employed in

the facilities owned and managed by the MOH and

the private health sector in 2022.

|

Table 3: Healthcare professionals

employed in health regions of the KSA,

2022

|

|

Health Region

|

Physicians

|

Number of Dentists

|

Nurses and midwives

|

Pharmacists

|

|

Taif

|

3184

|

731

|

5919

|

952

|

|

Jeddah

|

10940

|

2942

|

15965

|

4473

|

|

Makkah

|

5551

|

1219

|

8263

|

1772

|

|

Riyadh

|

20385

|

6279

|

38442

|

10995

|

|

Al-Ahsa

|

3197

|

720

|

6754

|

770

|

|

Eastern

|

9627

|

2248

|

19302

|

2866

|

|

Qaseem

|

4275

|

1112

|

8692

|

1544

|

|

Madina

|

5527

|

1418

|

10892

|

1571

|

|

Tabouk

|

2340

|

553

|

4511

|

802

|

|

Bishah

|

1154

|

259

|

1957

|

245

|

|

Aseer

|

4591

|

1307

|

8251

|

1639

|

|

Hafr Al Baten

|

1136

|

331

|

3528

|

315

|

|

Najran

|

1740

|

377

|

3620

|

409

|

|

Jazan

|

3440

|

729

|

6863

|

1169

|

|

Northern

|

1509

|

253

|

3177

|

339

|

|

Hail

|

2269

|

575

|

4541

|

697

|

|

Qunfudah

|

789

|

161

|

1138

|

175

|

|

Qurayyat

|

512

|

146

|

1958

|

123

|

|

Al-Jouf

|

1486

|

280

|

3830

|

314

|

|

Al Baha

|

1588

|

318

|

2354

|

239

|

|

Total

|

85240

|

21958

|

159957

|

31409

|

Source: Compiled from the Annual Statistical

Yearbook, MOH, KSA,2022.

(Data relates to health professionals employed by

the MOH and private sector)

A thorough

examination of the distribution of healthcare

professionals 10000 people in 20 health regions in

the KSA provides valuable information about the

healthcare system (Table 4).

|

Table 4: Physicians, Dentists, Nurses,

and Pharmacists per 10,000 population in

Health Regions

|

|

Region

|

Population

|

Physicians

|

Dentists

|

Nurses and Midwives

|

Pharmacists

|

|

Taif

|

1101571

|

28.90

|

6.63

|

53.73

|

8.64

|

|

Jeddah

|

3971816

|

27.54

|

7.41

|

40.19

|

11.26

|

|

Makkah

|

2677810

|

20.72

|

4.55

|

30.85

|

6.62

|

|

Riyadh

|

8591748

|

23.73

|

7.31

|

44.74

|

12.79

|

|

Al-Ahsa

|

1104267

|

28.95

|

6.52

|

61.16

|

6.97

|

|

Eastern

|

3553980

|

27.08

|

6.32

|

54.31

|

8.06

|

|

Qaseem

|

1336179

|

31.99

|

8.32

|

65.05

|

11.55

|

|

Madina

|

2137983

|

25.85

|

6.63

|

50.94

|

7.34

|

|

Tabouk

|

886036

|

26.41

|

6.24

|

50.91

|

9.05

|

|

Bishah

|

309528

|

37.28

|

8.36

|

63.22

|

7.92

|

|

Aseer

|

1714757

|

26.77

|

7.62

|

48.11

|

9.56

|

|

Hafr Al Baten

|

467007

|

24.32

|

7.08

|

75.54

|

6.74

|

|

Najran

|

592300

|

29.37

|

6.36

|

61.11

|

6.91

|

|

Jazan

|

1404997

|

24.48

|

5.18

|

48.84

|

8.32

|

|

Northern

|

373577

|

40.39

|

6.77

|

85.04

|

9.07

|

|

Hail

|

746406

|

30.39

|

7.70

|

60.83

|

9.33

|

|

Qunfudah

|

270266

|

29.19

|

5.95

|

42.11

|

6.47

|

|

Qurayyat

|

195016

|

26.25

|

7.48

|

100.40

|

6.31

|

|

Al-Jouf

|

400806

|

37.07

|

6.98

|

95.55

|

7.83

|

|

Al Baha

|

339174

|

46.82

|

9.37

|

69.40

|

7.04

|

|

Total

|

32175224

|

26.49

|

6.82

|

49.71

|

9.76

|

Source: Calculated by the authors based on MOH

data (Data relates to health professionals

employed by the MOH and private sector)

A comparison between

ratios of regional and national healthcare

professionals highlights significant disparities.

When it comes to regional distribution, 7 health

regions have a physician population ratio below

the national average, 9 regions have dentists

below the national level, and 4 regions have

nurses and midwives population ratio below the

national average, and 14 health regions have a

pharmacists-population ratio below the national

average. Health regions such as Riyadh, Makkah,

and Madina, have low physician-population ratios

compared to other regions, whereas regions like

Bishah, Northern, Al-Baha, and Al-Jouf show the

highest ratios at the opposite end of the

spectrum. This is in sharp contrast to the

country's average, showing a notable lack of

physicians, dentists, nurses, midwives, and

pharmacists in some regions. Further investigation

is needed on the distribution and accessibility of

resources for each population and their impact on

the effectiveness of delivering healthcare

services. The policymakers need to carefully

consider the empirical data to achieve the goals

of Saudi Vision 2030 and meet the needs of the

expanding Saudi population.

Equity in the distribution of healthcare

professionals

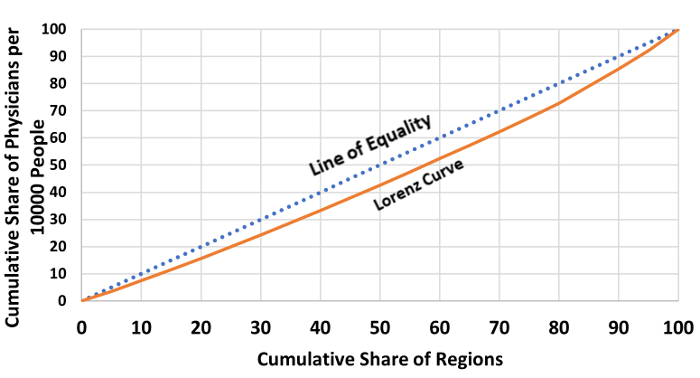

The distribution of

physicians in different regions of the KSA is even

as shown by Gini coefficient of 0.11. Fig 1 shows

the Lorenz curve, demonstrating the distribution

plotting the cumulative share of physicians

against the cumulative share of regions. The

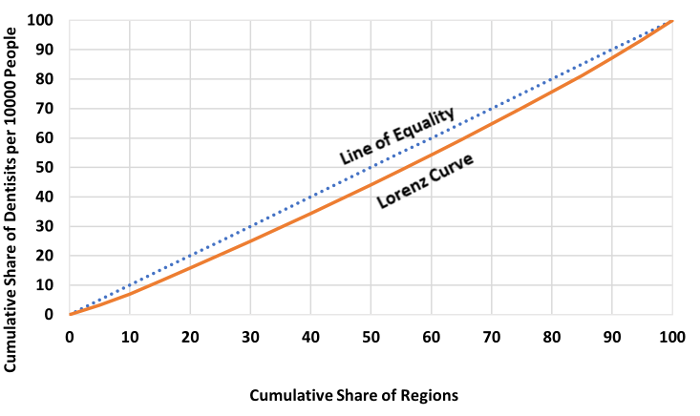

distribution of dentists in health regions shows a

Gini coefficient of 0.08 denotes an even

distribution of dentists across different regions

(Fig:2). The shape of the curve to the line of

equality indicates a perfect equality in the

distribution of dentists across all health

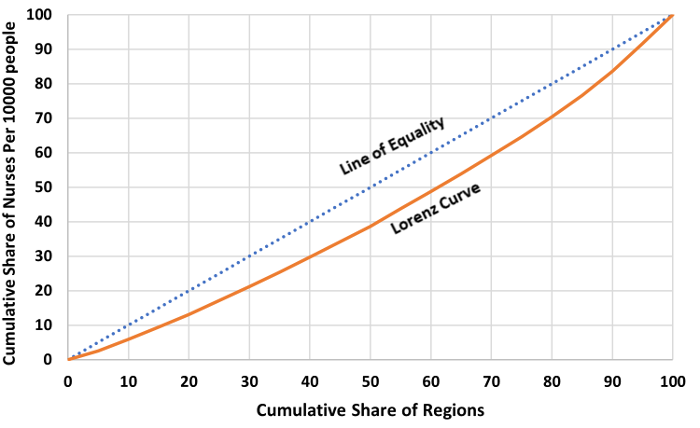

regions. The Gini coefficient of nurses and

midwives of 0.16 is slightly higher than

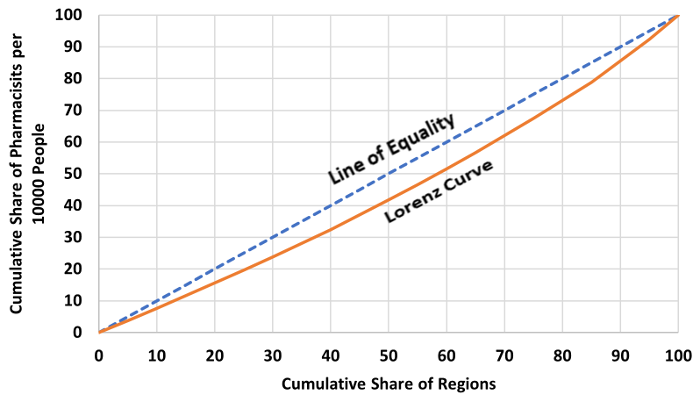

physicians and dentists (Fig 3). Similarly, the

Gini coefficient for pharmacists is 0.12, showing

an even distribution across the regions. These

Gini coefficients suggest a fair distribution of

physicians, nurses, and pharmacists across

regions, ensuring reasonably fair healthcare

access nationwide.

|

| Figure

1: Lorenz Curve showing the distribution

of physicians per 10,000 people in KSA

|

|

| Figure 2: Lorenz Curve

showing the distribution of dentists per

10,000 people in KSA |

|

| Figure 3: Lorenz Curve

showing the distribution of nurses and

midwives per 10,000 people |

|

| Figure 4: Lorenz Curve

showing the distribution of pharmacists

per 10,000 people |

Projection on the Enhancement in

Healthcare Professionals Distribution

An analysis was

conducted to assess healthcare professionals'

density across health regions in the KSA compared

to the global threshold level [36 ] aiming for a

minimum of 20.7 physicians, 8.2 dentists, 70.6

nurses and midwives, and 9.4 pharmacists per 10000

people to achieve the UHC index of 80 out of 100.

The analysis shows that all 20 health regions have

achieved the threshold level of physicians.

However, except for 2 regions namely Qaseem, and

Al Baha all regions registered a shortfall of

dentists below the threshold level. While 16

health regions have nurses and midwives below the

threshold level of 70.6 nurses and midwives per

10000 people; 15 regions have pharmacists fall

short of the threshold level of 9.4 pharmacists

per 10,000 people. Table 5 shows the current gaps

in distribution by region and the additional

number of dentists, nurses (including midwives),

and pharmacists required for each region to reach

the threshold level to achieve the UHC index of 80

out of 100. Figure 5 shows the shortage of health

professionals by administrative regions of the

KSA.

|

Table 5: Dentists, nurses, and

pharmacists needed to achieve the

threshold level

|

|

Health regions

|

Dentists needed to achieve a threshold

level (8.2 per 10,000 people)

|

Nurses and midwives needed to achieve a

threshold level (70.6 per 10,000 people)

|

Pharmacists needed to achieve a threshold

level of (70.6 per 10,000 people)

|

|

Required

|

Shortage

|

Percent

|

Required

|

Shortage

|

Percent

|

Required

|

Shortage

|

Percent

|

|

Taif

|

903

|

172

|

19.04

|

7777

|

1858

|

23.89

|

1035

|

84

|

8.11

|

|

Jeddah

|

3256

|

315

|

9.67

|

28041

|

12076

|

43.06

|

3733

|

+

|

+

|

|

Makkah

|

2196

|

977

|

44.48

|

18905

|

10642

|

56.29

|

2517

|

745

|

29.60

|

|

Riyadh

|

7045

|

766

|

10.87

|

60657

|

22216

|

36.62

|

8076

|

+

|

+

|

|

Al-Ahsa

|

905

|

186

|

20.55

|

7796

|

1042

|

13.36

|

1038

|

268

|

25.81

|

|

Eastern

|

2914

|

666

|

22.85

|

25091

|

5789

|

23.07

|

3341

|

475

|

14.22

|

|

Qaseem

|

1096

|

+

|

+

|

9433

|

+

|

+

|

1256

|

+

|

+

|

|

Madina

|

1753

|

335

|

19.11

|

15094

|

4202

|

27.83

|

2010

|

439

|

21.84

|

|

Tabouk

|

727

|

174

|

23.93

|

6255

|

1744

|

27.88

|

833

|

31

|

3.72

|

|

Bishah

|

253

|

5

|

1.97

|

2185

|

228

|

10.43

|

291

|

46

|

15.80

|

|

Aseer

|

1406

|

99

|

7.04

|

12106

|

3855

|

31.84

|

1612

|

+

|

+

|

|

Hafr Al Baten

|

383

|

52

|

13.57

|

3297

|

+

|

+

|

439

|

124

|

28.24

|

|

Najran

|

486

|

109

|

22.42

|

4183

|

562

|

13.43

|

557

|

148

|

26.57

|

|

Jazan

|

1152

|

423

|

36.71

|

9919

|

3056

|

30.80

|

1321

|

152

|

11.50

|

|

Northern

|

306

|

53

|

17.32

|

2637

|

+

|

+

|

351

|

12

|

3.41

|

|

Hail

|

612

|

37

|

6.04

|

5270

|

729

|

13.83

|

701

|

5

|

0.71

|

|

Qunfudah

|

221

|

61

|

27.60

|

1908

|

770

|

40.35

|

254

|

79

|

31.10

|

|

Qurayyat

|

159

|

14

|

8.80

|

1376

|

+

|

+

|

183

|

60

|

32.78

|

|

Al-Jouf

|

328

|

49

|

14.93

|

2830

|

+

|

+

|

377

|

63

|

16.71

|

|

Al Baha

|

278

|

+

|

+

|

2394

|

41

|

1.71

|

319

|

80

|

25.07

|

|

Total

|

26379

|

4483

|

|

227154

|

68810

|

|

30244

|

2811

|

|

Note: + refers to not required

or excess.

|

| Figure

5: Administrative regions with shortage of

healthcare professionals |

The research

highlighted the additional requirements for 4493

dentists, 69551 nurses and midwives, and 2811

pharmacists to adhere to the global threshold

level of 8.2 dentists, 70.6 nurses and midwives,

and 9.4 pharmacists per 10000 population in

different regions to reach the UHC index of 80.

Discussion

To the best of our

understanding, this is the initial research that

assesses the equity in the distribution of

healthcare professionals based on population size

among different health regions in the KSA in 2022.

From the analysis and results of the Gini

coefficient, it appears the distribution of

physicians, dentists, nurses, and pharmacists is

equitable across various regions in the KSA. The

Gini coefficients obtained for physicians,

dentists, nurses, and pharmacists are 0.11, 0.08,

0.16, and 0.12 respectively. Nevertheless, a stark

contrast in terms of healthcare professionals is

apparent when analyzing the 20 health regions in

comparison to the national averages of doctors,

dentists, nurses, and pharmacists. Roughly 65% of

the regions have physicians below the national

average, whereas 50% of regions have dentists

below the national level. While 30% of regions

have nurses and midwives below the national level,

a majority of the health regions (85%) have

pharmacists below the national average.

Notably, regions

such as Riyadh, Makkah, and Madina exhibit

significantly lower physician population ratios in

contrast to regions such as Bishah, Northern, and

Al Baha. This underscores the geographical

inequalities in the distribution of physicians.

The distribution of dentists across regions

reveals regions like Qaseem, Bishah, and Al Baha

have a higher number of dentists per 10,000

people, in contrast to regions like Mecca, Jazan,

and Qunfudah. While regions like Jeddah, Makkah,

Riyadh, and Qunfudah have a lower nurse and

midwives population ratio compared to the national

average, Qurayyat and Al-Jouf regions have nurses

and midwives double the national average. This

highlights the uneven distribution of healthcare

professionals across different geographical

regions in the KSA.

The study also

highlighted those significant economic regions

such as Makkah, Jeddah, Riyadh, and Madina showed

a lower healthcare professionals population ratio

compared to other regions. Makkah region, the

Holiest place for Muslims attract millions of

pilgrims and surge in visitors put enormous

pressure on healthcare system in the region [37].

It should also be noted that this region recorded

the high prevalence of COVID-19 cases in 2020,

constituting 49.3% of all cases in the Kingdom.

Makkah region faced inadequate availability of

healthcare resources including physicians, and ICU

hospital beds during the pandemic [38]. Therefore,

enhancing the availability of healthcare resources

including healthcare professionals distribution in

this region should be given higher priority.

Similarly, the study

showed that health regions such as Jeddah and

Riyadh have a low ratio of physicians, dentists,

nurses and pharmacists, highlighting a notable

shortage of the health professionals. Several

factors like population growth, increasing

economic activities, and urbanization in these

health regions pose challenges in effectively

providing access to healthcare services [31,39].

Despite their economic significance, these regions

lag in health professional distribution [32].While

specific numbers of health professionals employed

in the OGH sector in Riyadh and Jeddah are not

provided, it can be inferred that these cities may

have a better supply of health professionals

compared to other regions due to their urban

status.

Furthermore,

imbalanced allocation of healthcare resources such

as hospital beds, healthcare professionals and

primary healthcare centers could significantly

influence health outcomes. Earlier studies have

identified the issues of access to healthcare

services such as inadequate capacity of primary

healthcare centres, and hospital beds in Jeddah

region [38]. A rapid urbanization in Riyadh region

also poses challenges in equal distribution of

healthcare resources in all clusters [40].

Therefore, a more detailed comprehension of the

causes of disparities in health resources

distribution in densely populated areas like

Jeddah and Riyadh regions is needed.

The Gini

coefficients showed good indicator of equality in

the distribution of healthcare professionals among

the 20 health regions. The coefficients for

physicians, dentists, nurses and midwives, and

pharmacists falls under perfect equality, which

implies the health regions in the KSA have

relatively fair distribution of healthcare

professionals comparable to their population. The

proximity to the line of equality suggests minimal

disparity in the distribution of healthcare

professionals. Few studies have highlighted

disparities in the distribution of primary

healthcare centres, and hospital beds across

various regions in the KSA. Al Sheddi et al (2023)

estimated the Gini coefficient, which measures

inequality, indicated relative equality in primary

healthcare centre distribution across the 20

health regions, with values between 0.2 and 0.3.

The study found certain regions exhibited

disparities, suggesting the need for more

equitable distribution to improve healthcare

access and outcomes [41]. A study by Saffer et al

(2021) showed variations in the distribution of

primary healthcare centers across health regions,

and within regions, specialized healthcare

professionals are concentrated in urban areas

[42].

The disparities in

the distribution of health professionals have

significant practical implications for healthcare

delivery in underserved regions. These

implications manifest in various ways, affecting

both the quality and accessibility of healthcare

services. The shortage of health professionals in

the regions may cause longer wait times for

appointments, increased travel distances for

patients seeking care, reliance on emergency

services for non-urgent care, delayed diagnoses

and treatments, particularly in critical and

emergency cases. The shortage of health

professionals would also lead to overworked

healthcare providers, potentially leading to

burnout and reduced quality of care [43-45].

Studies have found the shortage of health

professionals may cause limited time for patient

consultations, affecting the thoroughness of

examinations and treatments, and insufficient

provision of preventive and primary care services

[45]. There are challenges in providing culturally

competent care, which is crucial for effective

healthcare delivery, and limited access to

specialists and advanced treatments in underserved

areas [44].

Authors have

estimated that additional requirements for 4493

dentists, 69551 nurses and midwives, and 2811

pharmacists to adhere to the global benchmark of

8.2 dentists, 70.6 nurses and midwives, and 9.4

pharmacists per 10000 people. This research has

also revealed that all health regions in the KSA

have achieved a threshold level of physicians of

20.7 per 10,000 people to achieve a UHC index of

80%. However, there are geographical inequalities,

particularly highly populated regions have lower

physician-population ratios compared to other

regions. The distribution of dentists across

health regions shows that Qaseem and Al Baha have

achieved a threshold level of 8.2 dentists per

10,000 people. With regard to the distribution of

nurses and midwives regions such as Hafr Al Baten,

Northern, Qurayyat, and Al Jouf have achieved a

threshold level of 70.6 nurses and midwives per

10,000 people. Regions like Jeddah, Makkah,

Riyadh, Qaseem, and Aseer have achieved a

threshold level of 9.4 pharmacists per 10,000

people.

Policy Implications

The study provides

several actionable insights that directly support

Saudi Vision 2030. It helps to identify potential

shortages or surpluses in health professionals in

the health regions. This information is crucial

for planning the healthcare workforce to meet the

changing needs of the population in health

regions. It also provides a roadmap for

policymakers to address future imbalances between

healthcare supply, and demand, directly supporting

the healthcare transformation goals of Saudi

Vision 2030. Future research incorporating GIS in

the spatial distribution of healthcare facilities

may provide a deeper understanding of

accessibility challenges. This data could be

extremely valuable for making precise policy

decisions and determining where to invest in new

healthcare infrastructure and improve access to

healthcare services. Future research should also

offer a foundation for a continuous dialogue and

investigation on methods to achieve a fairer

allocation of healthcare resources including

healthcare professionals in the KSA and create a

system that can adapt to the changing healthcare

needs of its people.

Study Limitations

Despite providing

valuable information on the distribution of

healthcare professionals in the KSA, this study

has certain limitations. The findings of this

study dependent on the accuracy and

comprehensiveness of the data from the MOH's

Statistical Yearbook 2022. Despite being a

reliable source, the MOH Yearbook may lack the

ability to accurately represent current changes or

the details of the health professionals. Moreover,

this research mainly focused on quantitative data,

neglecting qualitative insights into the reasons

behind workforce disparities. Qualitative data is

crucial for understanding the context and

underlying factors contributing to workforce

disparities. Secondary data often fails to account

for cultural and social factors that may influence

workforce disparities, such as gender roles or

regional differences in employment opportunities.

The Gini coefficient does not consider that

individuals may utilize health services in nearby

regions. This constraint is especially concerning

in areas with varying population densities, as it

could overestimate inequality in sparsely

populated regions.

Furthermore, the

focus of this research is restricted to 2022,

offering a snapshot rather than a longitudinal

view. Thus, the analysis does not consider the

trends in the distribution of healthcare

professionals over time or the effects of recent

reforms in the Saudi healthcare system. To address

these limitations, it would be beneficial to

complement the MOH data with qualitative studies

that explore the experiences and perspectives of

healthcare professionals, employers, and

policymakers. This approach would provide a more

comprehensive understanding of workforce

disparities and help inform more effective

policies and interventions in Saudi Arabia's

healthcare sector.

Conclusion

This research

highlights a critical component in the progress of

the KSA's healthcare system, characterized by the

challenge of balancing rapid economic development

with the equitable distribution of health

resources. The results showed notable differences

in health professionals’ availability in various

regions, especially in densely populated areas

such as Makkah, Riyadh, and Jeddah, underscoring

the shortfall in addressing the healthcare

requirements of the whole population. This

imbalance not only reflects the current state of

healthcare availability but also raises concerns

about the system's readiness to manage the growing

NCDs and the requirements of an aging population.

Therefore, addressing these inequalities will be

crucial for achieving Saudi Vision 2030 and

improving overall healthcare provision across the

country. Nonetheless, this research provides

valuable insights into the present status of

healthcare professionals' distribution in the KSA.

The existing inequalities amongst the health

regions can be reduced by introducing strategies

such as providing additional incentives,

increasing the retirement age in remote regions,

introducing bridge programs to upgrade the skills

of diploma-holding nurses, and expanding digital

health services. Additional strategies may include

investing in medical education, adopting policies

to increase the number of Saudi nationals in the

workforce, and implementing measures to improve

distribution across regions and between urban and

rural areas. These strategies collectively aim to

create a more equitable distribution of health

professionals across Saudi Arabia and improve

access to quality healthcare for all citizens

regardless of their location.

References

- Pan J, Shallcross D. Geographic distribution

of hospital beds throughout China: a

county-level econometric analysis. Int J

Equity Health 2016;15(1):179.

doi:10.1186/s12939-016-0467-9.

- Liu J, Eggleston K. The association between

health workforce and health outcomes: a

cross-country econometric study. Soc Indic

Res 2022;163(2):609-632.

- Basu S, Berkowitz S A, Phillips R L.

Association of primary care physician supply

with population mortality in the United States,

2005-2015. JAMA Intern. Med 2019;

179(4): 506–514.

- Wu Q, Wu L, Liang X, Xu J, Wu W, Xue Y.

Influencing factors of health resource

allocation and utilization before and after

COVID-19 based on RIF-I-OLS decomposition

method: a longitudinal retrospective study in

Guangdong Province, China. BMJ Open

2023;13(3):e065204.

- Ferretti F, Mariani M, Sarti E. Physician

density: will we ever close the gap? BMC Res

Notes 2023;16(1):84.

- Peters DH, Garg A, Bloom G, Walker DG, Brieger

W R, Rahman M H. Poverty and access to health

care in developing countries. Ann. N. Y.

Acad. Sci2008; 1136(1): 161–171.

- Leonard C, Stordeur S, Roberfroid D.

Association between physician density and health

care consumption: A systematic review of the

evidence. Health Policy.

2009;91(2):121-134.

- Omrani-Khoo H, Lotfi F, Safari H, Zargar

Balaye Jame S, Moghri J, Shafii M. Equity in

distribution of health care resources;

assessment of need and access, using three

practical indicators. Iran J Public Health.

2013;42(11):1299–308

- Mobaraki H, Hassani A, Kashkalani T,

Khalilnejad R, Chimeh EE. Equality in

distribution of human resources: the case of

Iran's ministry of health and medical education.

Iran J Public Health 2013;1:42.

- Sebai ZA, Milaat WA, Al-Zulaibani AA. Health

care services in Saudi Arabia: past, present and

future. J Family Community Med

2001;8(3):19–23.

- Rice N, Smith PC. Ethics and geographical

equity in health care. J Med Ethics

2001;27(4):256–61

- El-Farouk A. Geographical distribution of

health resources in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

: is it equitable? Egypt J Environ Change.

2016;8:4–20.

- Munga MA, Mæstad O. Measuring inequalities in

the distribution of health workers: the case of

Tanzania. Hum Resour Health 2009;7:4

(2009). Available at https://human-resources-health.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1478-4491-7-4.

- Nussbaum C, Massou E, Fisher R, Morciano M,

Harmer R, Ford J. Inequalities in the

distribution of the general practice workforce

in England: a practice-level longitudinal

analysis. BJGP Open.

2021;5(5):BJGPO.2021.0066. doi:

10.3399/BJGPO.2021.0066.

- Wang Y, Li Y, Qin S, Kong Y, Yu X, Guo K, Meng

J. The disequilibrium in the distribution of the

primary health workforce among eight economic

regions and between rural and urban areas in

China. Int J Equity Health 2020; 19:28 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-1139-3

- Wiseman V, Lagarde M, Batura N, Lin S, Irava

W, Roberts G. Measuring inequalities in the

distribution of the Fiji Health Workforce. Int

J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):115. doi:

10.1186/s12939-017-0575-1.

- Albejaidi F, Nair KS. Building the health

workforce: Saudi Arabia's challenges in

achieving Vision 2030. Int J Health Plann

Manage 2019;34(4):e1405-e1416. doi:

10.1002/hpm.2861

- Al-Hanawi MK, Khan SA, Al-Borie HM. Healthcare

human resource development in Saudi Arabia:

emerging challenges and opportunities—a critical

review. Public Health Rev 2019;40(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-019-0112-4.

- Ministry of Health, Statistical Yearbook.

Riyadh. Ministry of Health. 2022, Kingdom of

Saudi Arabia.

- World Health Organization. The Global Health

Observatory. https://www.who.int/data/gho.

- Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia's Vision

2030. http//www.vosion2030.gov.sa/en/ntp.

- Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia's

National Transformation Program.

https://vision2030.gov.sa / sites/default/

files/NTP_En.pdf.

- Alasiri AA, Mohammed V. Healthcare

transformation in Saudi Arabia: an overview

since the launch of Vision 2030. Health

Serv Insights 2022;3. doi: 10.1177/ 11786

329 2211 21 214.

- Albejaidi F, Nair K S. Nationalisation of

health workforce in Saudi Arabia’s public and

private sectors: a review of issues and

challenges. J Health Manag. 2021; 23(3).

Available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/09720634211035204

- Boettiger DC, Lin TK, Almansour M, Hamza MM,

Alsukait R, Herbst CH, et al.

Projected impact of population aging on

non-communicable disease burden and costs in the

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2020–2030. BMC

Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):1381.https://

doi. org/ 10. 1186/ s12913- 023- 10309-w.

- Mansour S. Spatial analysis of public health

facilities in Riyadh Governorate, Saudi Arabia:

a GIS-based study to assess geographic

variations of service provision and

accessibility. Geo Spatial Inform Sci.

2016;19(1):26–38.

- Nasiri A, Amerzadeh M, Yusefzadeh H, Moosavi

S, Kalhor R. Inequality in the distribution of

resources in the health sector before and after

the Health Transformation Plan in Qazvin, Iran.

J Health Popul Nutr 2024;43(1):4. doi:

10.1186/s41043-023-00495-y.

- Chen M, Chen X, Tan Y, Cao M, Zhao Z, Zheng W

et al. Unraveling the drivers of inequality in

primary health-care resource distribution:

Evidence from Guangzhou, China. Heliyon 2024;10(19):e37969.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e37969

- Chai Y, Xian G, Kou R, Wang M, Liu Y, Fu G, et

al. Equity and trends in the allocation

of health human resources in China from 2012 to

2021. Arch Public Health 2024;82:175. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-024-01407-0

- Dong E, Sun X, Xu T, Zhang S, Wang T, Zhang L,

et al. Measuring the inequalities in

healthcare resource in facility and workforce: A

longitudinal study in China. Front. Public

Health. 2023;11:1074417. doi:

10.3389/fpubh.2023.1074417

- Hawsawi T, Abouammoh. Distribution of hospital

beds across Saudi Arabia from 2015 to 2019: a

cross-sectional study. EMHJ

2022;28(1):23-30.

- Kattan W. The state of primary healthcare

centers in Saudi Arabia: A regional analysis for

2022. PLoS One 2024; 19(9): e0301918. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0301918.

- Kattan W, Alshareef N. 2022 Insights on

hospital bed distribution in Saudi Arabia:

evaluating needs to achieve global standards. BMC

Health Serv Res 2024;24(1):911. doi:

10.1186/s12913-024-11391-4.

- Bellu LG, Liberati P. Inequality analysis: The

Gini Index. 2005. Available at https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/a5e207ae-bff6-4a26-84b6-6108e318e706/content

- Joe Hasell. Measuring inequality: what is the

Gini coefficient? Published online at

OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from:

'https://ourworldindata.org/what-is-the-gini-coefficient'

[Online Resource]. 2023.

- Haakenstad A, Irvine CMS, Knight M, Bintz C,

Aravkin AY, Zheng P, et al. Measuring

the availability of human resources for health

and its relationship to universal health

coverage for 204 countries and territories from

1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis for the

global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet

2022; 399: 2129–54.

- Alrefaei AF, Almaleki D, Alshehrei F, et al.

Assessment of health awareness and knowledge

toward SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 vaccines among

residents of Makkah. Saudi Arabia Clin

Epidemiol Glob Health. 2022;13:100935.

https:// doi. org/ 10. 1016/j. cegh. 2021.

100935.

- Arbaein TJ, Alharbi KK, Alfahmi AA, Alharthi

KO, Monshi SS, Alzahrani AM, et al.

Makkah healthcare cluster response, challenges,

and interventions during COVID-19 pandemic: a

qualitative study. J Infect Public Health. 2024;17(6):975–85.

- Murad A, Faruque F, Naji A, Tiwari A, Qurnfula

E, Rahman M, et al. Optimizing health

service location in a highly urbanized city:

multi-criteria decision making and P-Median

problem models for public hospitals in Jeddah

City, KSA. PLoS ONE 2024;19(1):e0294819.

- Alhomaidhi A. Geographic distribution of

public health hospitals in Riyadh. Saudi

Arabia Geogr Bull. 2019;60(1):25–48.

- Al-Sheddi A, Kamel S, Almeshal AS, Assiri AM.

Distribution of primary healthcare centers

between 2017 and 2021 across Saudi Arabia. Cureus

2023;15(7):e41932. https:// doi. org/ 10. 7759/

cureus. 41932.

- Al Saffer Q, Al-Ghaith T, Alshehri A, Mohammed

R, Homidi S, Hamza MM, et al. The

capacity of primary healthcare facilities in

Saudi Arabia: infrastructure, services, drug

availability, and human resources. BMC

Health ServRes 2021;21(365). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06355-x.

- Acharya S. The challenges of healthcare

delivery in low-resource settings. J

Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2023;6(5):172

- Alharthi NA, Alharthi TH, Alzaidi AM,

Althobaiti SW, Alosimi MM, Hummadi MA et al.

Addressing the nursing workforce shortage in

Saudi Arabia: a multi-faceted approach. Migrat.

Lett. 2022;19 S5(2022).354-359.

- Michaeli DT, Michaeli JC, Albers S, Michaeli

T. The healthcare workforce shortage of nurses

and physicians: practice, theory, evidence, and

ways forward. Policy Politics Nurs. Pract. 2024;25(4):216-227.

|