|

Introduction

Achalasia

is a primary esophageal motility disorder

characterized by the failure of the lower

esophageal sphincter (LES) to relax in response to

swallowing, along with weak to absent esophageal

peristalsis. This disorder is uncommon, though

well documented in literature for over 300 years

(1), and causes a significant impairment of eating

ability, thereby adversely impacting the quality

of life (2).

The

pathophysiological basis of this disorder include

a loss of inhibitory function affecting the

esophageal myenteric nerves which result in loss

of esophageal peristalsis and inadequate

relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter

(LES), thereby resulting in a functional

obstruction (2).Rarely, in advanced cases, the

condition may manifest as a “sigmoid esophagus,”

which is a term that has been coined to describe

the dilation and distortion of the cervical

esophagus (3).

In this report, we

present one such case of a 36-year-old male in

whom sigmoid esophagus was successfully diagnosed

and then managed by a minimally invasive surgical

approach uneventfully. The case is presented

because of the rare nature of this disorder.

Case Presentation

A 36-year-old male

reported with persistent burning sensation in the

chest, difficulty in swallowing food and

regurgitation of undigested food, off and on, for

more than a year. He had been consuming

over-the-counter H2 blockers and proton pump

inhibitors but achieving partial relief only. He

had no significant past medical or surgical

history. He was a non-smoker and had no

addictions.

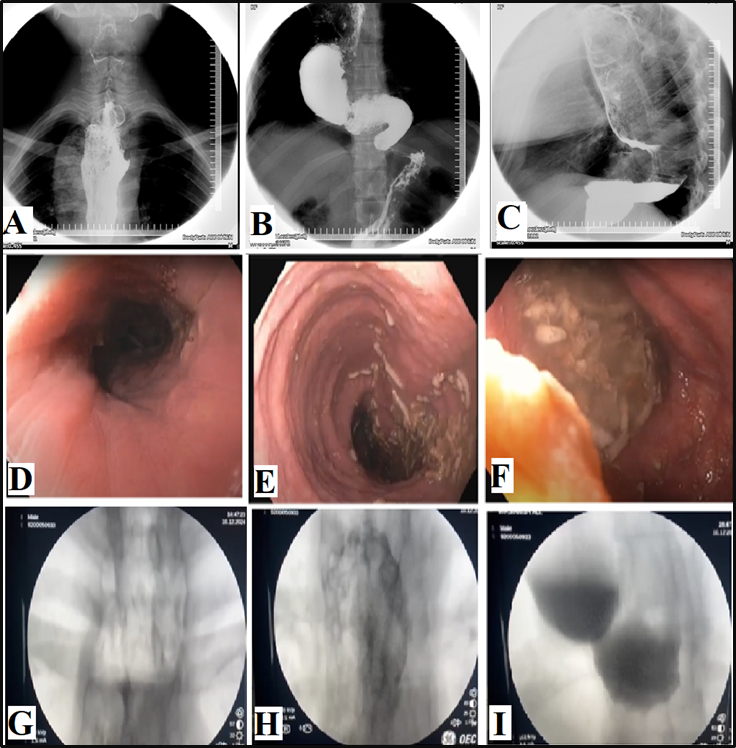

A barium

esophagogram (Figures A, B, and C) revealed a

significantly dilated esophagus with tapering of

the distal esophagus. Esophageal mucosa displayed

irregular distortion with focal areas of

hypertrophy, but no definite pouch or diverticula

was noted. Incomplete LES relaxation was

demonstrated that was not coordinated with

esophageal contraction, followed by uncoordinated,

non-propulsive, tertiary contractions.

Furthermore, there was a failure of normal

peristalsis to clear the esophagus of barium when

the patient lay in the recumbent position, with no

identification of primary waves. There were no

persistent filling defects, abnormal shouldering,

nor any evidence of hiatus hernia.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

(EGD) revealed a dilated esophagus with a very

tight lower esophageal sphincter (Figures D, E,

and F). No ulcerative or mass lesion was seen. The

findings were deemed to be consistent with

achalasia cardia. The patient was attached to the

services of a tertiary care facility with

board-certified upper gastrointestinal surgeons.

An axial CT scan of the chest with contrast was

advised, which revealed marked dilatation of the

entire esophagus (maximum 87 mm) down to the

gastroesophageal junction with stagnant food and

fluid levels. The entire dilated esophagus

appeared folded with diffuse wall thickening with

mass effect upon the related mediastinum

structures and lung parenchyma. After proper

counselling, laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy (LHM)

procedure was undertaken as a definitive

management option. The postoperative phase was

uneventful. At six months after surgery, the

patient was asymptomatic and highly satisfied with

the outcomes. A Gastrografin esophagogram study

was undertaken under fluoroscopic guidance (Figure

1 G, H, I). There was evidence of a dilated

esophagus with a tortuous and dilated lower third

of the esophagus with minimal pooling of contrast

in its tortuous segment and decreased peristalsis.

However, there was free passage of contrast into

the stomach and small bowel loops. No gross

filling defect or esophageal web was documented.

|

| Figure

1: A, B, C - Preoperative Barium

esophagogram; D, E, F – Preoperative

esophagogastroduodenoscopy; G, H, I –

Postoperative (6 months) Gastrografin

esophagogram study, undertaken under

fluoroscopic guidance. |

Discussion

Achalasia is a very

rare disorder, with an incidence and a prevalence

of about 1 per 100000 population and 10 per

100000, respectively. The disease is found across

all the races and equally in both the genders. The

patients typically present between the second and

the fifth decade of life, though 2%-5% of cases do

occur in the paediatric age group (4).

The successful

transport of food from the mouth to the stomach,

while preventing its reflux from the stomach, is a

result of the coordinated peristalsis in the

pharynx and esophagus along with the relaxation of

the upper and lower esophageal sphincters (LES),

brought about by the modulatory action of the

parasympathetic excitatory and inhibitory pathways

(myenteric plexus) that innervate the smooth

muscles of the lower esophageal sphincter.

Patients with achalasia lack the inhibitory

ganglion cells while retaining the normal

excitatory neurons and thence suffer from an

imbalance of inhibitory and excitatory

neurotransmission with a resultant non-relaxed

hypertensive LES (3). Functional obstruction

ensues, and gradually the esophagus dilates,

leading to uncoordinated aperistalsis and

worsening obstructive symptoms (2,3), as is

evident in the imaging studies (Figure 1) of our

presented case report.

The majority of

patients with achalasia present with dysphagia

and/or regurgitation. Other symptoms include chest

discomfort, nocturnal cough, heartburn, hiccups,

and weight loss. When achalasia is suspected, a

barium esophagogram (barium swallow) is conducted,

which reveals the smooth tapering of the lower

esophagus to a “bird’s beak” appearance, with

dilatation of the proximal esophagus, lack of

peristalsis during fluoroscopy, and an air-fluid

level (5). In advanced disease, a sigmoid-like

appearance of the esophagus may be visible, as was

seen in the images recorded in the presented case

(Figure 1 A-C). Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD)

is recommended in all patients presenting with

dysphagia to exclude any neoplastic lesions

involving the esophagus (6). EGD otherwise has low

accuracy in the diagnosis of achalasia and may not

reveal any abnormal normal findings in the earlier

stages of the disease. In advanced cases, the

esophagus may appear dilated, tortuous, and

atonic, with retained food contents, as was

documented in our presented case (Figure 1 D, E,

F). High-resolution esophageal manometry (HRM) is

a sensitive test for the diagnosis of achalasia

and reveals an increase in pressure of the LES

with incomplete relaxation in response to

swallowing and, in most cases, a lack of

coordinated peristalsis in the lower esophagus

(7). Manometric findings can aid in the

determination of prognosis and appropriate

treatment modalities.

Once malignancy has

been ruled out, management aims at easing the

symptoms of achalasia by decreasing the outflow

resistance through nonsurgical or surgical

modalities (8-9). The nonsurgical options are

effective in early stages and include

pharmacotherapy, endoscopic botulinum toxin

injection, and pneumatic dilatation, whereas the

surgical options include laparoscopic Heller

myotomy (LHM) and peroral endoscopic myotomy

(POEM). In our case, LHM was conducted

uneventfully, and the patient was symptom-free at

6 months follow-up after surgery. In LHM, the

circular muscle fibers running across the lower

esophageal sphincter are cut, leading to

relaxation (9) . LHM can potentially cause

uncontrolled gastroesophageal reflux, so it

typically pairs with an anti-reflux procedure

(partial fundoplication). The clinical success

rate of LHM is reported to be high (76 to 100%) at

three years, with a low mortality rate of 0.1%.

Even after successful treatment, the patients

require long-term follow-up because all available

treatments are palliative, making recurrences

common, and secondly, there is a small risk of

malignancy (7-10).

Conclusion

Sigmoid esophagus is

a manifestation of an advanced stage of achalasia.

It is rare in occurrence. After ruling out

malignancy, laparoscopic Heller myotomy is an

effective and safe management option.

Postoperatively, the patients require long-term

follow-up for early detection of recurrence,

reflux, or malignancy.

Acknowledgements

The patient provided

us with his case history and photos for academic

purposes, including publishing in a peer-reviewed

journal, for which the authors are grateful.

References

- Kraichely RE, Farrugia G. Achalasia:

physiology and etiopathogenesis. Dis

Esophagus. 2006;19(4):213-23.

- Furuzawa-Carballeda J, Torres-Landa S,

Valdovinos MÁ, Coss-Adame E, Martín Del Campo

LA, Torres-Villalobos G. New insights into the

pathophysiology of achalasia and implications

for future treatment. World J Gastroenterol.

2016 Sep 21;22(35):7892-907.

- Vallejo C, Gheit Y, Nagi TK, Suarez ZK, Haider

MA. A Rare Case of Achalasia Sigmoid Esophagus

Obstructed by Food Bolus. Cureus. 2023

Sep 19;15(9): e45567.

- Wadhwa V, Thota PN, Parikh MP, Lopez R, Sanaka

MR. Changing trends in age, gender, racial

distribution and inpatient burden of achalasia.

Gastroenterology Res. 2017

Apr;10(2):70-77.

- Fisichella PM, Raz D, Palazzo F, Niponmick I,

Patti MG. Clinical, radiological, and manometric

profile in 145 patients with untreated

achalasia. World J Surg. 2008

Sep;32(9):1974-9.

- Laurino-Neto RM, Herbella F, Schlottmann F,

Patti M. Evaluation of esophageal achalasia:

from symptoms to the Chicago classification. Arq

Bras Cir Dig. 2018;31(2): e1376.

- Torresan F, Ioannou A, Azzaroli F, Bazzoli F.

Treatment of achalasia in the era of

high-resolution manometry. Ann

Gastroenterol. 2015

Jul-Sep;28(3):301-308.

- Eckardt AJ, Eckardt VF. Current clinical

approach to achalasia. World J

Gastroenterol. 2009 Aug

28;15(32):3969-75.

- Genc B, Solak A, Solak I, Serkan Gur M. A rare

manifestation of achalasia: huge esophagus

causing tracheal compression and progressive

dyspnea. Eurasian J Med. 2014

Feb;46(1):57-60.

- Gyawali CP. Achalasia: new perspectives on an

old disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016

Jan;28(1):4-11.

|