|

Introduction

Gestational

diabetes mellitus (GDM) is defined as glucose

intolerance of varying severity that occurs first

time, or is first detected during pregnancy [1].

Prevalence of GDM is 7% of all pregnancies in the

world [2]. GDM is one of the leading causes of

morbidity and mortality in both mother and

new-borns worldwide [3]. In India, its prevalence

is found to vary in urban and rural areas.

However, a recent study by Choudhary et al

reported a prevalence of 9% in India [4].GDM is

commonly associated with infections of the urinary

tract.

Asymptomatic

bacteriuria (ASB) refers to the presence of

bacteria in the urine without any symptoms of a

UTI, while pyuria is the presence of an elevated

number of white blood cells in the urine,

indicating potential inflammation or infection in

the urinary tract. Both conditions are important

to consider when evaluating urinary tract health

and may require further investigation and

management, depending on the individual's clinical

characteristics and risk factors.

Urine culture is

considered the gold standard for diagnosing ASB.

It involves incubating urine samples on culture

media to detect bacterial growth. The presence of

a significant colony count of a single

uropathogenic organism typically indicates ASB.

Urine culture is generally highly sensitive,

capable of detecting low bacterial loads, and is

considered the benchmark for assessing sensitivity

of other techniques. The specificity of urine

culture is also high as it can differentiate

between pathogenic and commensal bacteria.

However, urine

culture has some limitations. It is

time-consuming, usually requiring 24 to 48 hours

for results. Additionally, some fastidious

bacteria may not grow on standard culture media,

leading to false negatives. Moreover, it may not

be practical in certain settings, such as

point-of-care testing.

Heparin-binding

protein (HBP) is a biomarker associated with

inflammation and tissue damage. ELISA-based assays

can measure the concentration of HBP in urine

samples, which may indicate the presence of

inflammation in the urinary tract. Specificity for

UHBP has been reported to be higher than

sensitivity in some studies, suggesting that false

positives might be less frequent. One limitation

of UHBP measurement is that elevated levels can be

seen in other inflammatory conditions, not

specific to ASB. Therefore, the diagnostic

accuracy of UHBP needs to be carefully assessed.

Multiplex PCR is a

molecular technique that can amplify and detect

DNA sequences of multiple bacterial species

simultaneously. It is highly sensitive and can

detect even low bacterial loads.

Urinary tract

infections (UTI) are one of the most common

infections resulting in a significant healthcare

expenditure. Pregnant women because of the

physiological changes are highly susceptible to

UTI [5]. During pregnancy, the treatment of UTI is

recommended even if there no accompanying

symptoms, i.e., Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB).

It has been claimed

ASB is three to four times more common in women

with diabetes than in healthy women [6].

Prevalence of ASB is reported to be as high as 30%

in diabetic women [7]. ASB is considered

clinically significant and worth treating during

pregnancy because treatment will effectively

reduce the risk of pyelonephritis and preterm

delivery [8]. UTI are dependent on the accurate

identification of pathogens. Even though urine

culture is the gold standard test, it takes 24-48

hours to give results. Some organisms can be

fastidious and therefore difficult to grow in

culture. So it is need of the hour to look for an

alternative urinary biomarker which correlates

with the urine culture results. It is also

important to look for a technique which gives

accurate results in a short time interval.

Further, PCR results can be obtained in a day or

less, while culture can require 2 or more days

[9]. In the present study, we compared three

different methods such as urine culture, Urinary

Heparin Binding Protein (UHBP) assay by ELISA and

identification of pathogens by multiplex PCR for

the diagnosis of ASB/UTI in GDM. Gestational

diabetes, which is a combination of pregnancy and

diabetes are at the high risk of ASB as well as

UTI. Therefore, it is justifiable to detect a

biomarker or technique which can detect ASB/UTI in

a short span of time.

Objectives:

- To find the prevalence of

asymptomatic bacteriuria/pyuria in gestational

diabetes mellitus

- To find the association between asymptomatic

bacteriuria/pyuria and urinary heparin binding

protein (UHBP)

- To compare sensitivities and specificities of

the techniques (urine culture and UHBP by ELISA

and multiplex PCR)

Methods

Study

design and participants:

We included 50 GDM

patients diagnosed based on 75 gm oral GTT (OGTT)

as per modified DIPSI criteria who are willing to

participate in this observational study. Samples

were collected from OBG department (OP & IP)

from Justice K. S. Hegde Charitable Hospital,

Deralakatte, Mangalore and the study was conducted

in Microbiology and Molecular genetics laboratory

of Central Research Lab, K. S. Hegde Medical

Academy, Nitte (Deemed to be University),

Mangaluru, Karnataka, India.

Exclusion

criteria and Ethics: Women with multiple

pregnancy, known pre-gestational diabetes,

pregnancies complicated by major foetal

malformations or known major cardiac, renal or

hepatic disorders were excluded.

Institutional

Ethics Committee approval was obtained prior to

the study. Written Informed Consents were taken

from the patients

Laboratory

Investigations

Urine

culture

Clean catch

midstream urine samples were collected into a

sterile screw capped urine container by standard

method. The samples were labelled and 0.2 mg of

boric acid was added to prevent the bacterial

growth in urine samples. The samples were cultured

on cysteine-lactose electrolyte deficient agar and

blood agar using a sterile 4 mm platinum wired

calibrated loop for the isolation of

microorganisms. The plates were incubated for

overnight at 37 °C and the samples were considered

positive when an organism cultured is at a

concentration of 10 5 CFU/mL which was

estimated through multiplying the isolated

colonies by 1000. The isolates were identified up

to the species level by standard biochemical

tests.

Antibiotic

sensitivity testing:

Antibiotic

sensitivity testing was performed by the modified

disc diffusion method. Inoculums adjusted to 0.5

McFarland standard was swabbed on Mueller Hinton

agar plates for antibiotic sensitivity assay.

Eight groups of antimicrobials such as Amoxyclav,

Cephalexin, Nitrofurantoin, Erythromycin,

Sulfisoxazole, Fosfomycin, Imipenem and

Trimethoprim / Sulfamethoxazole were selected and

sensitivity pattern was tested.

Estimation

of UHBP by ELISA

Tubes were

centrifuged within 1 hour of sampling at 3000 rpm

for 10 minutes, and separate aliquots of the

supernatant were stored at -20°C until analysis

for UHBP. UHBP was estimated using ELISA.

Characterization

of Pathogen by Multiplex PCR

DNA Extraction

and Analysis

DNA was extracted

from urine samples using the MagMAX DNA

Multi-Sample Ultra Kit. One ml of urine sample was

added into 2.0ml collection tube. Centrifuged for

2 minutes at 13,000 rpm. The supernatant was

discarded completely. The pellet obtained was

resuspended using 200μl of Resuspended Solution

(1X PBS) (ML116) and mixed well. 20μl of RNase A

solution was added, mixed and incubated for 2

minutes at room temperature (15-25ºC). Cell lysis

was carried out by adding 20μl of Proteinase K

solution followed by 200μl of Lysis solution to

the re-suspended pellet. Mixed for 15 minutes

using a Vertex. Incubated for 10 minutes at 70ºC.

200μl of ethanol (96-100%) was added to the lysate

and mixed with help of vertex for 5 to 10 seconds.

Lysate obtained was transferred to the HiElute

Miniprep Spin Column. Centrifuged at 10,000 rpm

for 1 minute. The flow through liquid was

discarded and the column was placed in a same

2.0ml collection tube. About 500μl of diluted wash

solution was added to the column and centrifuged

at 10,000 rpm for 1 minute. The flow- through

liquid was discarded and the same collection tube

was re-used with the column. Again 500μl of

diluted wash solution was added to the column and

centrifuge at 13,000 for 3 minutes to dry the

column. The column was centrifuged for another 1

minute at same speed to dry the residual ethanol

(as required). 200μl of Elution buffer was added

directly onto the column, incubated for 1 minute

at room temperature (15-25ºC). Centrifuged at

10,000 rpm for 1 minute to elute the DNA. The

isolated DNA was transferred to a fresh 2ml

collection tube with a cap and stored -20ºC.

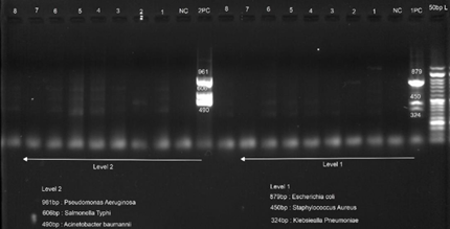

Multiplex PCR

HiMedia’s Hi-PCR

Sepsis Pathogen Semi-Q PCR Kit (Multiplex) was

used for the amplification of specific gene using

specific primers in a single tube reaction. The

PCR Master mix was prepared as indicated in the

Table1 . Components listed in the table 1

were added to centrifuge tube and was centrifuged

at 6000rpm for about 10 seconds. The tubes were

placed in MiniAmp Plus Thermal cycler and PCR

program was set as listed in the Table 2

. For analysis of the PCR data, 10μL of amplicon

were loaded on a 1.5% agarose gel (incorporated

EtBr) along with 1μL of 6X Gel loading buffer. 3μL

of 50bp DNA ladder was used. Organisms detected

and their band sizes are listed in the Table

3.

|

Table 1: Protocol for PCR

Master mix preparation

|

|

Components

|

Volume (μL) to be added for 1R (for a

50μL reaction)

|

|

Tube 1

|

Tube 2

|

|

2 X PCR TaqMixture

|

25 μL

|

25 μL

|

|

Sepsis Primer Mix 1

|

6 μL

|

_

|

|

Sepsis Primer Mix 2

|

_

|

6 μL

|

|

Template DNA/Positive Control/ Negative

control

|

5 μL

|

5 μL

|

|

Total volume

|

Up to 50 μL

|

Up to 50 μL

|

|

Table 2: PCR program

|

|

Initial denaturation

|

94ºC 3 minutes

|

|

denaturation

|

94ºC 1 minute

|

|

Annealing

|

58ºC 1 minute

|

|

Extension

|

72ºC 1 minute

|

|

Final Extension

|

72ºC 5 minutes

|

|

Table 3: Data

interpretation.

|

|

Organism

|

Band size

|

|

E. coli

|

879bp

|

|

S. aureus

|

450bp

|

|

K. pneumonia

|

324bp

|

|

P. aeruginosa

|

961bp

|

|

S. typhi

|

606bp

|

|

A. baumannii

|

490bp

|

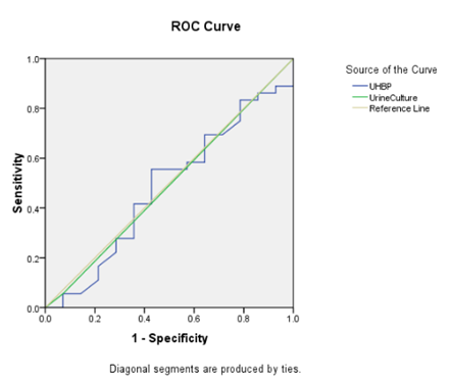

Statistical

Analysis

The statistical

analysis was carried out with SPSS 21.0. and

GraphPad Prism 9. Receiver operating

characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed to

compare sensitivities, specificities, positive

predictive values and negative predictive values

of the three techniques.

Results

Total of 50

patients with GDM were enrolled during first year

with the mean age of 29.3±4.27years. Their mean

FBS value was 157 ± 17.2 mg/dl. Prevalence of ASB

among GDM patients on basis of urine culture is

listed in Table 5. Prevalence of ASB

among GDM patients on basis of Multiplex PCR is

demonstrated in Table 6. A significant

association was noted between detection of

organisms and multiplex PCR findings compared to

urine culture (p <0.0001) as indicated in

Table 7 .

|

Table 5:

Prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria

in GDM as per urine culture

|

|

Name of organism

|

N

|

%

|

|

Acinetobacter lowffi

|

1

|

2

|

|

Enteroco fecalis

|

1

|

2

|

|

Klebsiella

|

1

|

2

|

|

Contaminant

|

1

|

2

|

|

Mixed flora

|

17

|

34

|

|

No Growth (NG)

|

7

|

14

|

|

Non-significant bacteria (NSB)

|

22

|

44

|

|

Table 6:

Prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria

in GDM as per Multiplex PCR

|

|

Name of organism

|

N

|

%

|

|

Acinetobacter baumanii

|

1

|

2

|

|

E. coli

|

2

|

4

|

|

E. coli + Acinetobacter

|

1

|

2

|

|

E. coli + Klebsiella + Acinetobacter

baumani + Pseudomonas

|

1

|

2

|

|

E. coli + Klebsiella + Salmonella

|

1

|

2

|

|

E. coli + Klebsiella +

Salmonella + Pseudomonas

aeroginosa

|

1

|

2

|

|

E. coli + Staphylococcus

aureus

|

3

|

6

|

|

Klebsiella

|

3

|

6

|

|

No growth

|

14

|

28

|

|

Staphylococcus aureus

|

13

|

26

|

|

Staphylcoccus aureus + E.

coli

|

1

|

2

|

|

Staphylococcus aureus + Klebsiella

|

9

|

18

|

Median (25% - 75%)

value of UHBP levels in urine was noted to be 689

(625, - 863) pg/ml. A significant association was

observed between UHBP levels and multiplex PCR

findings with (p= 0.017) (Table 7). No association

was found between UHBP levels and urine culture

reports (p<0.99) (Table 8).

|

| Fig

1: Agarose gel image of Multiplex PCR

|

|

Table 7:

Association of asymptomatic

bacteriuria between Multiplex PCR

findings and Urine culture findings.

|

|

Growth detected

|

Total

|

|

Multiplex PCR

|

Urine culture

|

|

Growth positive

|

36

|

3

|

39

|

|

Growth negative

|

14

|

47

|

61

|

|

Total

|

50

|

50

|

100

|

|

Table 8:

Association of asymptomatic bacteriuria

between UHBP levels and Multiplex PCR

findings

|

|

UHBP levels (pg/ml)

|

Multiplex PCR findings

|

Total

|

|

culture +ve

|

Culture -ve

|

|

<870

|

8

|

4

|

12

|

|

>870

|

10

|

28

|

38

|

|

Total

|

18

|

32

|

50

|

|

Test: Fisher’s exact test

|

|

Table 9: Association of

asymptomatic bacteriuria between UHBP

levels and Urine culture

|

|

UHBP levels (pg/ml)

|

Urine Culture findings

|

Total

|

|

culture +ve

|

Culture -ve

|

|

<870

|

3

|

35

|

38

|

|

>870

|

0

|

12

|

12

|

|

Total

|

3

|

47

|

50

|

|

Test: Fisher’s exact test

Sensitivity: 0.7200, Specificity: 0.9400,

Positive Predictive Value: 0.9231,

Negative Predictive Value: 0.7705,

Likelihood ratio: 12.00 (Method used:

Wilson Brown)

|

|

| Fig

2: ROC for Urine culture and UHBP, taking

multiplex PCR as gold standard |

AUC for the

Receiver operating characteristic curves (ROC) of

UHBP was 0.480 and that of urine culture was

0.492. Cut off value of UHBP was 675 pg/ml.

Discussion

Studies reported

the prevalence of ASB in GDM range from 4-18%

which is higher compared to the prevalence of ASB

in pregnancy without diabetes which range from

4.6-8.2%[10]. In our present study, the prevalence

of ASB in GDM as per urine culture was found to be

6%. The prevalence of ASB in GDM as per multiplex

PCR is higher compared to the urine culture.

Multiplex PCR also identified polymicrobial

infection (34%) accurately compared to urine

culture. Polymicrobial infection can result in

antibiotic resistance, therefore identification of

specific organism is of great clinical

significance [11]. Even though urine culture is

considered as the gold standard for the diagnosis

of ASB it takes 24-48 hours to get the results,

whereas PCR detected pathogens even in samples

which were negative for growth in urine culture in

a rapid and accurate way. As indicated in

Table 7,a significant association was

noted between detection of organisms and multiplex

PCR findings compared to urine culture (p

<0.0001). Out of 47 growth negative samples

from urine culture, whereas only 14 samples were

showed negative growth in multiplex PCR. This

further support the previously reported studies

that multiplex PCR can be used effectively to

detect UTI similar to urine culture and therefore

multiplex PCR is noninferior to urine culture for

detection of UTI [9,11].

Heparin-binding

protein (HBP) is a pro-inflammatory protein stored

in secretory and azurophilic granules of

neutrophils. Activated neutrophils release HBP

which acts as a chemoattractant, activates

monocytes and induces vascular leakage [12]. UHBP

was found to be more sensitive and specific for

UTI than the presence of leukocyturia and can be

used as a diagnostic marker for UTI in adults

[13]. However the potential of UHBP as a

diagnostic marker in ASB is not clear. In the

present study, UHBP levels in urine was noted to

be 689 (625, - 863) pg/ml. UHBP levels in urine

was significantly associated with multiplex PCR

results, but the association with urine culture

results was found to be non-significant. These

results further indicates that multiplex PCR

results are more specific compared to urine

culture results.

By taking multiplex

PCR as gold standard AUC for the ROC of UHBP was

0.480 and that of urine culture was 0.492. Cut off

value of UHBP was 675 pg/ml. These results suggest

the limitation of urine culture along with delay

in results. Multiplex PCR was found to be more

sensitive and specific compared to Urine culture

and estimation of UHBP.

In recent years,

researchers have been exploring the potential role

of urinary heparin binding protein (HBP) as a

biomarker for UTIs and inflammatory conditions.

HBP is a protein involved in the immune response

and is released by activated neutrophils, a type

of white blood cell, during inflammation. Its

presence in the urine may indicate inflammation

and tissue damage in the urinary tract. The

association between ASB/pyuria and urinary HBP in

the context of gestational diabetes is an area of

interest, as it could provide insights into the

pathophysiology of UTIs during pregnancy and

potentially lead to the development of better

diagnostic and management strategies.

A study published

by Mardh et al reported the association between

urinary HBP and ASB in pregnant women. The

researchers collected urine samples from pregnant

women with and without ASB and measured the levels

of urinary HBP using an ELISA-based assay. The

study found that pregnant women with ASB had

significantly higher levels of urinary HBP

compared to those without ASB, suggesting a

potential link between urinary HBP and the

presence of bacterial colonization in the urinary

tract during pregnancy[14].

Another study by

Cobo et al, examined the association between

urinary HBP and pyuria in pregnant women [15]. The

study found a positive correlation between the

levels of urinary HBP and the presence of pyuria,

indicating that HBP may be a potential biomarker

for inflammation and infection in the urinary

tract during pregnancy. (Reference:

Mardh et al have

shown variable sensitivities for UHBP in detecting

ASB, reporting a sensitivity of 84% for UHBP in

pregnant women with ASB [14].

Studies have shown

high sensitivities for multiplex PCR in detecting

ASB. For instance, A study Park et al reported a

sensitivity of 91% for multiplex PCR in detecting

ASB in a diverse population [16]. One drawback of

PCR-based methods is that they do not distinguish

between live and dead bacteria, potentially

leading to false positives in cases of past

infections or contamination.

Comparative studies

have been conducted to assess the diagnostic

performance of these three techniques. A study by

Jo et al compared the diagnostic accuracy of UHBP

measurement by ELISA and multiplex PCR for

detecting ASB in elderly patients [17]. The

researchers found that UHBP had a sensitivity of

81.5%, while multiplex PCR had a sensitivity of

93.4%. The specificity of UHBP and multiplex PCR

was 72.1% and 79.2%, respectively. The study

concluded that multiplex PCR had higher

sensitivity but lower specificity compared to UHBP

measurement.

Another study by

Mardh et al compared the diagnostic performance of

urine culture, UHBP measurement by ELISA, and

multiplex PCR in detecting ASB in pregnant

women[18]. The researchers reported a sensitivity

of 84% for UHBP measurement, 100% for multiplex

PCR, and 81% for urine culture. The specificities

for UHBP measurement, multiplex PCR, and urine

culture were 83%, 82%, and 100%, respectively. The

study suggested that UHBP measurement and

multiplex PCR had comparable sensitivities, but

urine culture had lower sensitivity (Reference:

Overall, multiplex

PCR appears to have higher sensitivity compared to

UHBP measurement and urine culture, making it a

promising technique for detecting ASB. However,

further research is needed to validate and compare

these methods in diverse populations and clinical

settings. Moreover, considering the cost,

availability, and turnaround time of each

technique is essential when choosing the most

suitable method for ASB detection.

Limitations

Limitations of the

existing research include relatively small sample

sizes, potential confounding factors, and the

cross-sectional nature of some studies, which

limits the ability to establish causality.

Additionally, the diagnostic accuracy and

threshold values for urinary HBP in detecting ASB

and pyuria need to be validated in larger and more

diverse populations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study suggest a potential

association between urinary HBP and ASB/pyuria in

gestational diabetes, more comprehensive research

is required to confirm and elucidate the nature of

this relationship. Future studies should focus on

larger cohorts, prospective designs, and

standardized measurement techniques to further

explore the role of urinary HBP as a potential

biomarker for UTIs during pregnancy and its

implications for gestational diabetes management.

Funding:

Research society for the study of diabetes in

India and Indian council of medical research.

References

- Metzger, BE. Long-term Outcomes in Mothers

Diagnosed With Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and

Their Offspring. Clinical Obstetrics and

Gynecology December 2007;50(4):972-979.

- Ferrara A, Kahn HS, Quesenberry CP, Riley C,

Hedderson MM. An increase in the incidence of

gestational diabetes mellitus: Northern

California, 1991-2000. Obstet Gynecol.

2004 Mar;103(3):526-33.

- Lee KW, Ching SM, Ramachandran V et al.

Prevalence and risk factors of gestational

diabetes mellitus in Asia: a systematic review

and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth

2018;18:494.

- Choudhary N, Rasheed M, Aggarwal V. Prevalence

of gestational diabetes mellitus, maternal and

neonatal outcomes in a peripheral hospital in

North India. Int J Res Med Sci

2017;5:2343-5.

- Ghouri F, Hollywood A, Ryan K. A systematic

review of non-antibiotic measures for the

prevention of urinary tract infections in

pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth.

2018 Apr 13;18(1):99.

- Rowe TA, Juthani-Mehta M. Urinary tract

infection in older adults. Aging Health. 2013

Oct;9(5):10.2217/ahe.13.38

- Renko M, Tapanainen P, Tossavainen P, Pokka T,

Uhari M. Meta-analysis of the significance of

asymptomatic bacteriuria in diabetes. Diabetes

Care. 2011 Jan;34(1):230-235.

- Schnarr J, Smaill F. Asymptomatic bacteriuria

and symptomatic urinary tract infections in

pregnancy. European Journal of Clinical

Investigation. 2008;38:50-57.

- Xu R, Deebel N, Casals R, Dutta R, Mirzazadeh

M. A New Gold Rush: A Review of Current and

Developing Diagnostic Tools for Urinary Tract

Infections. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021

Mar 9;11(3):479.

- Schnarr J, Smaill F. Asymptomatic bacteriuria

and symptomatic urinary tract infections in

pregnancy. Eur J Clin Invest. 2008

Oct;38 Suppl 2:50-7.

- Wojno KJ, Baunoch D, Luke N, et al. Multiplex

PCR Based Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) Analysis

Compared to Traditional Urine Culture in

Identifying Significant Pathogens in Symptomatic

Patients. Urology. 2020

Feb;136:119-126.

- Linder A, Soehnlein O, Akesson P. Roles of

heparin-binding protein in bacterial infections.

J Innate Immun. 2010;2(5):431-8.

- Kjölvmark C, Påhlman LI, Åkesson P, Linder A.

Heparin-binding protein: a diagnostic biomarker

of urinary tract infection in adults. Open

Forum Infect Dis. 2014 Apr

23;1(1):ofu004.

- Mårdh E, Brauner A, Söderquist B, et al.

Urinary heparin-binding protein in pregnant

women with asymptomatic bacteriuria. Eur J

Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018

Feb;221:154-158. doi:

10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.12.029.

- Cobo T, Rodríguez-Ortega M, Pérez-Bosque A, et

al. Association between pyuria and urinary

heparin-binding protein levels in pregnant women

with pre-gestational diabetes. Am J Reprod

Immunol. 2019 Oct;82(4):e13197. doi:

10.1111/aji.13197.)

- Park KH, Kim YJ, Jeong YJ, et al. Comparison

of the Urinary Microbiota Between Women with

Interstitial Cystitis and Healthy Controls. J

Clin Microbiol. 2015 Aug;53(8):2624-2631.

doi: 10.1128/JCM.00877-15.).

- Jo J, Lee K, Rhee JE, et al. Comparison of

diagnostic accuracy of urine dipstick and urine

heparin-binding protein in elderly patients with

asymptomatic bacteriuria. J Clin Microbiol.

2017 Jun;55(6):1865-1871. doi:

10.1128/JCM.00154-17.

- Mårdh E, Brauner A, Söderquist B, et al.

Urinary heparin-binding protein, a new

diagnostic marker for asymptomatic bacteriuria

in pregnant women: a multicentre cohort study. BMC

Infect Dis. 2016 Apr 12;16:198. doi:

10.1186/s12879-016-1546-4.

|