|

Introduction

In

India, tuberculosis (TB) is a serious public

health concern with 2.42 million cases were

reported in 2022, an increase of 13% from 2021,

which indicates the highest number of cases ever

reported in a single nation.(1–8) The bacterium

that causes TB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis,

has undergone genetic mutations over time, leading

to drug resistance and the emergence of novel

variants that present significant obstacles to the

control or management of the TB

epidemic.(1,3,4,8–14) Drug-resistant tuberculosis

(DR-TB) is primarily classified into two

categories: multidrug-resistant TB (MTB) and

extensively drug-resistant

TB(XDR).(3–5,9,12,14–16) The MDR-TB refers to TB

strains that are resistant to at least two of the

most powerful first-line drugs, isoniazid and

rifampicin.(3,8,12,14) The patient with XDR-TB, on

the other hand, is resistant to isoniazid,

rifampicin, and at least three of the six main

classes of second-line drugs (e.g., aminoglycosides,

polypeptides, fluoroquinolones, thioamides,

cycloserines, and para-aminosalicylic acid).(12,15)

The India TB Report divides DR-TB into four

categories based on the type of drug resistance

(Fig. 1).(4,17) In India, the DR-TB cases have

risen from 2012 by 17402 to 91841 in 2022 (Fig.

2).(7) However the incidence of DR-TB incidence

has significantly increased since 2012, but get

slightly decline between the COVID-19 waves that

started in 2020 (72787 Cases) and 2021 (70787

cases) (Fig. 2).(7,18–21) Numerous factors,

including a history of TB treatment, limited

access to diagnostic and treatment facilities,

lost follow-up, co-infection with HIV infection,

subpar healthcare infrastructure, insufficient

funding for TB control programmes, and ineffective

policies and strategies, have been associated with

the emergence of DR-TB in India.(3,10,12,22,23)

|

| Fig

1: Different types of DR-TB are divided

into four categories, as described by the

India TB Report 2023. |

|

| Fig

2: Year-wise reported incidence of

different types of DR-TB in India. |

Demography and Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis

The prevalence of

DR-TB varies by region, age, and gender, according

to a several studies carried out in India among

various populations.(1,2,6,8,9,12–14,22–28) Men

are 3.5 times more likely than women to be exposed

to the risk of developing DR-TB because of their

frequent drinking and smoking habits. It has been

noted that DR-TB risk factors vary by

gender.(6,24,26–29) Additionally, Maharashtra,

Gujarat, and Uttar Pradesh accounted for 48% of

all cases of DR-TB in the country in 2022.(7) In

comparison to other age groups, DR-TB is becoming

more common in economically active age groups

(18–54 years).(1,6,8,9,14,16,22–29) As a result of

the drug regimen used to treat DR-TB being linked

to a higher risk of treatment failure, relapse,

and mortality, which manifests in higher rates of

morbidity and mortality and also reported to have

high risk of developing DR-TB, particularly in

young children and pregnant

women.(1,2,12,15,26,30) One of the main reasons

among children of pediatric age for the

development of DR-TB is close contact with DR-TB

patients. (6,7,13)

Poverty and drug

resistance are major interconnected challenges

that significantly impact the fight against TB in

India. Patients with DR-TB often belong to lower

or middle socioeconomic classes and face various

socio-economic challenges.(22–27,29) They are more

likely to be married, come from joint households

(i.e., with more than four individuals), and have

limited education, with the majority having only a

high school attainments.(22–27,29) These people

frequently live in crowded rural areas, use

traditional smoke appliances to cook (i.e., Chulha),

and work as labourers.(22–27,29) Their

socioeconomic status, combined with a lack of

knowledge about TB treatment, puts them at a

higher risk of developing DR-TB.(23,25–27,29)

Furthermore, poverty exacerbates the problem by

resulting in poor nutrition, overcrowding, and a

lack of education and awareness, all of which

weaken the immune system and increase

vulnerability to TB infection and the development

of DR-TB.(22–26,28,29)

Objective

The main goal of

this in-depth review study is to evaluate and

comprehend the DR-TB epidemic's precarious

situation. The goal of the study is to examine the

difficulties encountered across India, such as the

demographics of those affected, the methods used

for diagnosis and treatment, and the policies and

programmes currently in place for the control of

DR-TB. The present study also aims to offer

insightful information on the epidemiology of

DR-TB, efficient clinical management techniques,

and public health approaches for addressing the

burden of DR-TB in India.

Methodology

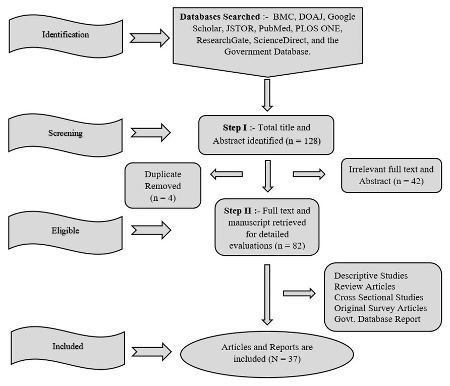

Utilizing a wide

range of international and national electronic

databases, including prestigious sources like BMC

journals, the Directory of Open Access Journals

(DOAJ), Google Scholar, JSTOR, PubMed, PLOS ONE,

ResearchGate, Science Direct, and the Government

Database, a thorough systematic diagnosis and

literature review were meticulously carried out.

The carefully selected search terms

"drug-resistant tuberculosis in India,"

"comorbidities associated with DR-TB," "treatment

challenges in DR-TB," and "DR-TB diagnosis

challenges" were used to ensure a thorough

examination of the literature that was already in

existence. Furthermore, pertinent technical

reports and government databases were carefully

identified and assessed while strictly adhering to

predetermined inclusion criteria to uphold the

results' integrity and reduce bias (Fig. 3). Also,

duplicate scientific papers yielded from different

search engines were excluded. The lengthy process

ended with the (N=37) downloading of the entire

manuscript, which included both the abstracts and

the full-length manuscripts. This allowed for the

interpretation, revision, and eventual completion

of this comprehensive review article.

|

| Fig

3: Steps to select the manuscripts and

complete this comprehensive review

article. |

Consequences of Drug-Resistant

Tuberculosis

Early TB detection

enables the development of an effective treatment

regimen, lowers the risk of future drug

resistance, and limits the

spread.(5,7,14,18–21,31) However, due to the

emergence of DR-TB, there are several problems

with treating TB, such as the cost of care, a lack

of diagnostic tools and laboratories, a higher

risk of transmission, newly identified M.

tuberculosis strains, ongoing mutations in

this bacteria, social stigma and discrimination,

social and economic issues, as well as other

related health issues.(2,8–10,12,28,30,32) The use

of additional therapies, such as second-line

therapies and injections, which are connected to

more detrimental side effects than conventional TB

treatment, is also one of the emerging causes of

DR-TB. (2,30) According to Shah et al. (2), Husain

et al. (30), and Kumar et al. (33), India

contributed to over one-fourth (26%) of the global

burden of DR-TB (in 2022), underscoring the

disease's rising prevalence and the difficulties

encountered in implementing the updated National

Strategic Plan, which aims to eradicate TB by

2025.(2,5,7,30,33) Contrarily, DR-TB therapy lasts

longer than 24–48 months compared to

drug-sensitive TB, making it more difficult, and

expensive for low- or middle-income families to

manage.(2,15,17,28,30,32) Due to the highly

contagious nature of DR-TB, patients must also be

isolated for longer periods of time. Additionally,

no close contacts should be present, as this could

increase the risk or vulnerability of the

situation.(15,17,28) The fact that patients and

caregivers experience social stigma and prejudice

while undergoing DR-TB therapy is one of the key

issues brought up by numerous research

investigation, primarily because of societal

misunderstandings, mistrust, misconceptions, and

myths.(2,12,28) The majority of DR-TB patients

experience social problems and feel helpless

because of their poor socioeconomic status and the

prolonged treatment of DR-TB, which exacerbates

their psychiatric comorbidities and makes

treatment more difficult.(15–17,28,29) The primary

causes of psychiatric comorbidities among DT-TB

are disease duration and literacy among the

vulnerable and caregivers.(28,32)

Comorbidities

associated with Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis

The TB epidemic with

associated comorbidities is vulnerable over time

and has challenging consequences and situations

for diagnosis and treatment, which eventually get

mutated into DR-TB.(1,15,16,28,29) Undernutrition,

HIV, diabetes, alcohol, and tobacco are major and

significant associated comorbidities among TB

patients that have a higher odds of emerging or

developing DR-TB.(1,15,16,28,29) These

comorbidities compromise the immune system,

increase the risk of treatment complications, and

contribute to the development of drug resistance.

In addition to the complexities of managing DR-TB,

patients suffering from comorbidities and vice

versa complicate overall health

outcomes.(1,15,16,28,29)

Undernutrition

Nutrient intake must

be appropriate to promote normal development,

growth, and overall health.(5,7,18–21) One of the

most pressing problems continues to be

undernutrition, which affects 663 million people

worldwide. (5) A few of the significant

contributors to undernutrition include poverty,

inadequate infant feeding and care practices, poor

maternal nutrition and health, and recurrent

illnesses.(5,7) Undernutrition is a significant

factor that amplifies the vulnerability of TB

patients to DR-TB and contributes to delayed

treatment, ultimately result in mortality. (1,14)

This is demonstrated by the fact that India ranked

107th out of 121 nations in the Global Hunger

Index in 2022. (5) Additionally, nutritional

deficiencies can lead to stunted growth, weakened

immune systems, cognitive impairments, and an

increased risk of TB.(1,14) Working with TB

patients during treatment is more challenging and

difficult because of undernutrition, which makes

it difficult for the body to maintain a strong

immune system.(1,7,14) It is difficult for the

National Tuberculosis Elimination Programme (NTEP)

to manage this dual burden in addition to the side

effects of DR-TB treatment because, according to

the India TB Report, a total of 7.38 lakh TB

patients are malnourished.(1,14) In a similar

vein, a large body of research indicates that

DR-TB is brought on by a number of factors, such

as weight loss, a BMI of less than 18.5 kg/m2,

a decrease in appetite, and issues with food

absorption during protracted and difficult TB

treatment. (1,7,14,27)

HIV

Human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a major global

public health issue with 40 million cases

worldwide, where India ranks in third place with

24 lakh cases of people living with

HIV.(5,7,16,34) However, HIV is a causative agent

of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS),

which affects directly the body's immune system

and makes it prevalent to get sick from diseases

like TB, which is one of the most dreadful viruses

ever because there is no cure for HIV

infection.(5,15,16,25,26,29,31,35) The most common

way of transmitting HIV is through unprotected sex

or through the exchange of body fluids like blood,

breast milk, semen, and vaginal fluid.(5,7,16,35)

Conversely, HIV infection gets worse when it gets

associated with diseases like TB and increases the

risk of ramifications that lead to

DR-TB.(5,14,15,25,26,29,31,35) Several studies

revealed that HIV-TB infection is dominant in

males, with an average age group of about 30–40

years and a higher frequency of drug resistance

among HIV-TB

patients.(5,7,16,18–21,25,26,29,31,35) In 2022,

the India National AIDS Control Programme (NACP)

and the NTEP monitored 37578 total HIV/TB

cases.(7)

Alcohol

Worldwide, drinking

alcohol has caused major negative health effects

for decades and has become a common behavior and

way of life.(5,7,18–21) The National Family Health

Survey (NFHS-5, 2019-21) in India found that

alcohol usage has had a substantial impact on

people of all ages and genders, increasing

societal and personal problems, especially in

rural areas. In addition, there are 160 million

alcohol users in the country who consume billions

of liters of alcohol annually, with the percentage

of users continuously rising each year.(5,7,34)

Contrarily, numerous studies have shown that

alcohol use disorders and TB worsen the illnesses

and constitute a dual burden, which makes things

critical and more complicated over time by causing

mutation which increases morbidity and mortality,

and ultimately leading to DR-TB.(14,29)

Ramifications may occur for people with DR-TB who

continue drinking while receiving

treatment.(25,26,29) Additionally, due to a lack

of social support, divorced or widowed TB patients

are more likely to experience depression and

anxiety, which can lead to alcohol use. This makes

it even harder for them to adhere to treatment and

increases their risk of developing

DR-TB.(17,26,29,32) The dual burden of alcohol and

DR-TB causes a major hindrance in the direction of

diagnosis and treatment, and can lead to mutations

within M. tuberculosis, eventually

resulting in DR-TB. This, in turn, leads to

treatment complications and, potentially,

mortality.(10,14,17,26,29,32)

Diabetes

Diabetes is a

chronic, metabolic disease characterized by

elevated levels of blood glucose, which lead over

time to serious damage to the heart, blood

vessels, eyes, kidneys, and nerves.(5,26,29,36)

Globally, 422 million people have diabetes, of

whom India contributes 77 million adults, and 25

million are at high risk of developing

diabetes.(5,7,26) Diabetes compromises the immune

system, making individuals more susceptible to TB

infection and progression.(7,26,29,36) However,

the majority of people do not know or are ignorant

of their diabetes status, and those who had

concomitant diabetes during prior TB treatment

episodes had eight times greater odds of getting

DR-TB.(7,26,35,36) Additional delays in treatment,

prolonged exposure to anti-TB drugs, and impaired

immune responses among diabetes patients lead to

ramifications and mortality.(14,15,26,29)

Furthermore, managing such a dual burden among

individuals exacerbates health outcomes,

ultimately leading to increased rates of morbidity

and mortality.(16,36)

Tobacco

The coexistence of

tobacco use has emerged as a significant public

health concern, leading to 8 million deaths

worldwide annually, with India accounting for 1.35

million of these deaths.(5) Nicotine, a highly

addictive substance present in tobacco, represents

a substantial risk factor for infection from any

airborne disease.(5,7,29) Furthermore, tobacco use

and exposure to toxic second-hand smoke have a

higher risk of getting infected with TB,

progression from infection to active TB disease,

increased risk of recurrence and death from TB

globally, and eventually lead to substantial

social and economic costs.(26,29) According to the

India TB report (2023) in 2022, across India,

around 2,10,543 TB patients were identified as

tobacco users, with 67157 being linked with

tobacco cessation services.(7) However, a number

of studies revealed that the common cause of

worsening the vulnerability of TB patients and

spreading DR-TB was a history of residing in

places with second-hand smoke and past tobacco

use, whether it was chewing or smoking.(26,27,29)

Moreover, the dual burden of such a kind of

disease in public health concerns potentially

impacting treatment outcomes and increasing the

burden on healthcare systems.(5,7,18–21,26,27,29)

Diagnosis and Treatment of

Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis

In India, DR-TB is

rapidly increasing, and healthcare professionals

are facing significant difficulties in diagnosing

and treating DR-TB, which has serious

ramifications.(2,12,15,23,24,30,37) It is

challenging to monitor, manage, and regulate DR-TB

treatment in pediatric patients.(4,6,13,15) In the

DR-TB cases in children, the dosage of second-line

anti-tuberculosis drugs was based on the patient's

body weight.(13,15) Additionally, due to the

frequent and severe toxicity profile of

second-line drugs, female DR-TB patients of

reproductive age are at increased risk for harm to

both themselves and their fetus.(6,13,15)

The NTEP has

intended to expand the DR-TB diagnostic service

network, diagnosis tests, monitoring services, and

efforts of stakeholders to enhance health

outcomes, support quality-assured diagnostic

services, and provide a specific role in providing

ambulatory care for

patients.(3,7,8,11,15,18–21,24,28,33,37) India's

“Drug-Resistant TB Diagnostic Service Network"

includes the National Tuberculosis Reference

Laboratory, Intermediate Reference Laboratories,

private laboratories, and private and government

treatment centers.(7) Despite this support system,

the main difficulties faced by healthcare

professionals are a lack of modern laboratory

infrastructure, qualified staff, and appropriate

facilities for handling and processing specimens

particularly in rural areas.(2,37) In addition to

the DR-TB diagnosis network, DR-TB is frequently

diagnosed using culture-based techniques; however,

this process takes at least 12 weeks to

complete.(23,24,30) However, due to their cost and

limited availability of rapid molecular testing

techniques, are difficult to use in rural

areas.(15,23,24,30,37) Patients with DR-TB may

experience psychiatric comorbidities, such as

anxiety and depression, because of financial

strain, misconceptions, familial obligations, and

emotional distress.(17,28,32) Non-pharmacological

interventions, such as psychological and emotional

support, psycho-education, and methods like muscle

relaxation, mindfulness, and keeping a thought

journal, are given by caregivers, numerous

agencies, institutions, private and public

organizations, and health professionals to treat

these psychiatric comorbidities.(17,28,32)

Policy and programmatic

responses to Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis

The DR-TB is a

growing global health problem, with 27% of

infections coming from just one country: India.

DR-TB is already a pandemic in India because of

this frightening incident. Despite this, the

Indian government has implemented a variety of

targeted initiatives (Fig 4), treatments, and

policies to deal with the rising prevalence of

DR-TB in the nation.(3,7,8,15,24,28,33,37) These

include encouraging stakeholder engagement,

strengthening health systems, putting patient

support and social protection in place,

implementing infection prevention and control

measures, and encouraging research and

innovation.(7,28,33,37) The main aim of the Indian

government is the RNTCP, which is currently called

the NTEP.(15,33,37) To improve the management of

DR-TB, the NTEP devised the programmatic

management of DR-TB (PMDT), which focuses on early

detection, diagnosis, and appropriate treatment of

DR-TB cases.(3,7,8,15) Under the NTEP, India

established the largest TB laboratory network in

the world, enabling rapid diagnostic methods to

conduct universal drug susceptibility testing

(UDST) under one roof to quickly and affordably

diagnose DR-TB.(3,7,24,33) "Liquid Culture Media''

and "Nucleic Acid Amplification Test" (CABNAAT and

TrueNat) are these rapid diagnostic tests,

particularly for detecting pediatric, HIV-TB, and

EPTB. Moreover, the "Line Probe Assay" is a more

precise and quick molecular DST assay to diagnose

MDR and XDR-TB.(3,4,7,13)

|

| Fig

4: Implemented different schemes and

policy to reduce incidence of DR-TB under

NTEP in India |

The Direct Observed

Treatment Short Plus (DOTS) treatment scheme

(internationally recommended) calls for giving new

DR-TB patients supervision for a period of six

months to ensure that drug intake is being

monitored.(5,7,15,18–21,33) However, insufficient

data and a lack of intensive monitoring make the

situation vulnerable in the TB epidemic with

DR-TB.(15,33) Furthermore, new anti-TB drugs (e.g.

Bedaquiline, Delaminid and Linezolid)

with additional monitoring were made available for

the treatment of DR-TB and demonstrated a

significantly improved patient outcome.(1,8,37) In

addition, the Indian government launched a TB-free

campaign in order to reduce stigma and

discrimination, implement new healthcare

facilities (e.g., proper ventilation, use of

masks, and isolation of patients), provide

appropriate training to healthcare professionals,

and raise awareness regarding highly contagious

DR-TB. Even though the world is evolving, chronic

illnesses like DR-TB still necessitate lengthy

treatment regimens that may cause family

disruptions and an increase in dropout rates and

child labour.(27,29,37) To provide supportive

compression and reduce the occurrence of DR-TB in

low- and middle-income households in March 2018,

the Direct Benefit Transfer Schemes were

introduced.(37) In accordance with this, 500 INR

is sent in stages to the patient's bank account

each month to provide for proper dietary support

and, as a reward during treatment, transportation

allowances.(27,33,37) Additionally, the Indian

government has taken steps to improve access to

healthcare, particularly in rural areas, using a

public-private partnership strategy. It has

included the private sector in joint NTEP

initiatives to improve access to care and reduce

the TB epidemic with DR-TB.(7,33) Furthermore, a

real-time web-based surveillance system known as

"Nikshay" "NikshayAushadi," and the Lab

Information Management System were established as

part of the NSP in order to improve surveillance,

implement robust reporting, and effectively

monitor treatment.(3,7,33)

Future Challenges of

Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis

Future efforts by

the Indian government to control the TB epidemic,

particularly regarding DR-TB, will face

significant challenges due to the high percentage

of latent TB cases.(7,18–21,33) The emergence of

new DR-TB strains, which can result from mutations

in the M. tuberculosis bacteria as a

result of comorbidities and environmental factors,

will be one of the biggest challenges.

(4,5,7–10,14,15,23,24,30,37) Strong strategies

will be required to halt the highly contagious

nature of these new DR-TB strains.(3,5,12,14–16)

To enable the early and precise detection of DR-TB

cases with a patient-centered approach, ongoing

research and development initiatives, monitoring

and social support, investments in cutting-edge

diagnostic technologies, laboratory

infrastructure, and campaigning will be

necessary.(15,28) To improve treatment outcomes

for people with DR-TB in India, significant

funding will also be required.

Conclusion

The emergence of

DR-TB, which continues to be a global public

health concern, has made affected populations more

vulnerable. The Indian government must implement a

multifaceted, multi-sectoral strategy to

effectively combat this epidemic. This entails

making sure that there is an ongoing supply of

efficient medications, putting in place routine

monitoring and assessment mechanisms to spot gaps

in the healthcare system, and collaborating with

various stakeholders like government

organizations, pharmaceutical firms, and academic

institutions to ensure thorough reporting and

prompt treatment of all DR-TB patients.

Collaboration with non-governmental organizations

and private partners is also necessary to address

issues like patient education, stigma, and

restricted access to healthcare in remote and

underserved areas. Regular campaigns and the

planning of free medical camps can aid in bringing

attention to the issue and helping those in need.

By putting these suggestions into practice, the

Indian government can effectively combat DR-TB and

lessen its effects on public health.

Acknowledgement

The authors

gratefully acknowledge the help and cooperation of

the Department of Anthropology, Sikkim University.

The present review study was financially supported

in the form of the University Grants

Commission-Non-NET Fellowship, and Sikkim

University is also being acknowledged.

References

- Salhotra VS, Sachdeva KS, Kshirsagar N, Parmar

M, Ramachandran R, Padmapriyadarsini C, et al.

Effectiveness and safety of bedaquiline under

conditional access program for treatment of

drug-resistant tuberculosis in India: An interim

analysis. Indian Journal of Tuberculosis.

2020;67(1):29–37.

- Shah I, Poojari V, Meshram H. Multi-Drug

Resistant and Extensively-Drug Resistant

Tuberculosis. Indian J Pediatr.

2020;87(10):833–9.

- Singh N, Singh AK, Kumar S, Narendra Pratap

Singh NPS, Gaur V. Role of Mycobacterial Culture

and Drug Sensitivity Testing Laboratory under

National Tuberculosis Elimination Program for

the Abolition of Tuberculosis in India by 2025.

Journal of Clinical Diagnostic Research

[Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 May 22]. Available

from: https://www.jcdr.net/articles/PDF/16655/55426_CE[Nik]_F(SHU)_PF1(AG_SS)_PFA(AG_KM)_PN(KM).pdf

- Khurana P, Saigal K, Ghosh A. Drug resistance

pattern and mutation pattern in pediatric

tuberculosis: Study from north India. Indian

J Tuberculosis 2021;68(4):481–4.

- WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2022

[Internet]. World Health Organization; 2022 Oct

[cited 2023 Jan 3] p. 68. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061729

- Dhamnetiya D, Arora S, Jha RP. Tuberculosis

burden in India and its control from 1990 to

2019: Evidence from global burden of disease

study 2019. Indian Journal of Tuberculosis.

2023;70(1):87–98.

- India TB Report 2023 [Internet]. India:

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government

of India; 2023 [cited 2023 Jan 5] p. 296.

Available from: https://tbcindia.gov.in/showfile.php?lid=3680

- Resendiz-Galvan JE, Arora PR, Abdelwahab MT,

Udwadia ZF, Rodrigues C, Gupta A, et al.

Pharmacokinetic analysis of linezolid for

multidrug resistant tuberculosis at a tertiary

care centre in Mumbai, India. Front

Pharmacol. 2023;13:1081123.

- Jain A, Singh PK, Chooramani G, Dixit P,

Malhotra HS. Drug resistance and associated

genetic mutations among patients with suspected

MDR-TB in Uttar Pradesh, India. Int J

Tuberc and Lung Dis. 2016;20(7):870–5.

- Swain SS, Sharma D, Hussain T, Pati S.

Molecular mechanisms of underlying genetic

factors and associated mutations for drug

resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Emerging Microbes and Infections.

2020;9(1):1651–63.

- Giri OP, Kumar A, Giri VP, Nikhil N. Impact of

Treatment Supporters on the Treatment Outcomes

of Drug Resistant-Tuberculosis (DR-TB) Patients:

A Retrospective Cohort Study. Cureus

[Internet]. 2022 Mar 6 [cited 2023 May

22]; Available from: https://www.cureus.com/articles/88412-impact-of-treatment-supporters-on-the-treatment-outcomes-of-drug-resistant-tuberculosis-dr-tb-patients-a-retrospective-cohort-study

- Aaina M, Venkatesh K, Usharani B, Anbazhagi M,

Rakesh G, Muthuraj M. Risk Factors and Treatment

Outcome Analysis Associated with Second-Line

Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Journal of

Respiration. 202128;2(1):1–12.

- Mannebach K, Dressel A, Eason L. Pediatric

tuberculosis in India: Justice and human rights.

Public Health Nursing.

2022;39(5):1058–64.

- Kiran B, Singla R, Singla N et al. Factors

affecting the treatment outcome of injection

based shorter MDR-TB regimen at a referral

centre in India. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis

[Internet]. 2022 Oct 5 [cited 2023 May 22]

- Prasad R, Singh A, Balasubramanian V, Gupta N.

Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in

India: Current evidence on diagnosis and

management. Indian J Med Res. 2017;145(3):271–93.

- Utpat K, Rajpurohit R, Desai U. Prevalence of

pre-extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (Pre

XDR-TB) and extensively drug-resistant

tuberculosis (XDR-TB) among extra pulmonary (EP)

multidrug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) at a

tertiary care center in Mumbai in pre

Bedaquiline (BDQ) era. Lung India.

2023;40(1):19.

- Laxmeshwar C, Das M, Mathur T, Israni T, Jha

S, Iyer A, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities

among patients with complex drug-resistant

tuberculosis in Mumbai, India. Dholakia YN,

editor. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(2):e0263759.

- India TB Report 2022 [Internet]. India:

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government

of India; 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 5] p. 263.

Available from: https://tbcindia.gov.in/WriteReadData/IndiaTBReport2022/TBAnnaulReport2022.pdf

- India TB Report 2019 [Internet]. India:

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government

of India; 2019 [cited 2023 Jan 5] p. 222.

Available from: https://tbcindia.gov.in/WriteReadData/India%20TB%20Report%202019.pdf

- India TB Report 2021 [Internet]. India:

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government

of India; 2021 [cited 2023 Jan 5] p. 329.

Available from: https://tbcindia.gov.in/showfile.php?lid=3587

- India TB Report 2020 [Internet]. India:

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government

of India; 2020 [cited 2023 Jan 5] p. 266.

Available from: https://tbcindia.gov.in/showfile.php?lid=3538

- Nair SA, Raizada N, Sachdeva KS, Denkinger C,

Schumacher S, Dewan P, et al. Factors Associated

with Tuberculosis and Rifampicin-Resistant

Tuberculosis amongst Symptomatic Patients in

India: A Retrospective Analysis. Subbian S,

editor. PLoS ONE. 2016 Feb

26;11(2):e0150054.

- Lohiya A, SuliankatchiAbdulkader R, Rath RS,

Jacob O, Chinnakali P, Goel AD, et al.

Prevalence and patterns of drug resistant

pulmonary tuberculosis in India—A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Journal of Global

Antimicrobial Resistance. 2020;22:308–16.

- Dzeyie KA, Basu S, Dikid T, Bhatnagar AK,

Chauhan LS, Narain JP. Epidemiological and

behavioural correlates of drug-resistant

tuberculosis in a Tertiary Care Centre, Delhi,

India. Indian Journal of Tuberculosis.

2019;66(3):331–6.

- Dorjee K, Sadutshang TD, Rana RS, Topgyal S,

Phunkyi D, Choetso T, et al. High prevalence of

rifampin-resistant tuberculosis in mountainous

districts of India. Indian Journal of

Tuberculosis. 2020;67(1):59–64.

- RivuBasu, Susmita Kundu, Debabani Biswas,

Saswati Nath, Sarkar A, Archita Bhattacharya.

Socio-Demographic and Clinical Profile of Drug

Resistant Tuberculosis Patients in a Tertiary

Care Centre of Kolkata. Indian J Community

Health. 2021;33(4):608–14.

- Ladha N, Bhardwaj P, Chauhan NK, Kh N, Nag VL,

Giribabu D. Determinants, risk factors and

spatial analysis of multi-drug resistant

pulmonary tuberculosis in Jodhpur, India. Monaldi

Arch Chest Dis [Internet]. 2022 Jan 18

[cited 2023 May 16]; Available from: https://monaldi-archives.org/index.php/macd/article/view/2026

- Nagarajan K, Kumarsamy K, Begum R, Panibatla

V, Reddy R, Adepu R, et al. A Dual Perspective

of Psycho-Social Barriers and Challenges

Experienced by Drug-Resistant TB Patients and

Their Caregivers through the Course of Diagnosis

and Treatment: Findings from a Qualitative Study

in Bengaluru and Hyderabad Districts of South

India. Antibiotics. 2022;11(11):1586.

- Sharma P, Lalwani J, Pandey P, Thakur A.

Factors associated with the development of

secondary multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int

J Prev Med. 2019;10(1):67.

- Husain AA, Kupz A, Kashyap RS. Controlling the

drug-resistant tuberculosis epidemic in India:

challenges and implications. Epidemiol

Health. 2021;43:e2021022.

- Ahmed S, Shukla I, Fatima N, Varshney S,

Shameem M, Tayyaba U. Profile of

drug-resistant-conferring mutations among new

and previously treated pulmonary tuberculosis

cases from Aligarh region of Northern India. Int

J Mycobacteriol. 2018;7(4):315.

- Srinivasan G, Chaturvedi D, Verma D, Pal H,

Khatoon H, Yadav D, et al. Prevalence of

depression and anxiety among drug resistant

tuberculosis: A study in North India. Indian

Journal of Tuberculosis. 2021;68(4):457–63.

- Kumar Sr, Shrinivasa B, Hissar Ss,

Rajasakthivel M. Ethical implications of the

National Tuberculosis Elimination Programme in

India: A framework-based analysis. Int J

Health Allied Sci. 2021;10(4):253.

- National Family Health Survey 2019-21

[Internet]. Government of India; 2021 [cited

2023 May 23]. Available from:

https://prsindia.org/policy/vital-stats/national-family-health-survey-5

- Mehta G, Sharma A, Arora SK. Human

Immunodeficiency Virus-1 Subtype-C Genetically

Diversify to Acquire Higher Replication

Competence in Human Host with Comorbidities. AIDS

Research and Human Retroviruses.

2021;37(5):391–8.

- Tegegne BS, Mengesha MM, Teferra AA, Awoke MA,

Habtewold TD. Association between diabetes

mellitus and multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis:

evidence from a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):161.

- Sachdeva KS, Parmar M, Patel Y, Gupta R,

Rathod S, Chauhan S, et al. Evolutionary journey

of programmatic services and treatment outcomes

among drug resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB)

patients under National TB Elimination Programme

in India (2005-2020). Expert Review of

Respiratory Medicine. 2021;15(7):885–98.

|