Introduction:

Sepsis was earlier defined as an infection caused by microbes that produces fever, tachycardia, tachypnoea and change in blood leukocytes. Sepsis is now being considered as life threatening organ dysfunction caused by dysregulation of host's systemic inflammatory and immune response to microbial invasion that produces organ injury.[1] Septic shock is a subset of sepsis in which underlying circulatory, cellular and metabolism abnormalities are profound enough to substantially increase mortality.[2] Septic shock is identified by persistent hypotension requiring vasopressors to maintain MAP ≥65mmHg and blood lactate >2mmol/l despite adequate fluid resuscitation.[3]

Many risk factors for sepsis are related to both the predisposition to develop an infection and once infection develops, the likelihood of developing acute organ dysfunction. Severe sepsis and septic shock contribute to significant morbidity and mortality in hospitalised patients.[4]

The outcome in septic shock depends on many factors such as the source of infection, time of start of first antibiotic, high SOFA scoring at the time of admission, the host response in the form of activation of immune system leading to inflammation that cause rise in various markers of inflammation.[4] However, mortality can be predicted from simple complete haemogram parameters which are easily accessible such as a high

neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, high platelet to lymphocyte ratio and mean platelet volume which must be assessed so as to provide early and adequate treatment at primary and secondary healthcare level which could lead to better outcome in sepsis and septic shock patients.[5]

It was planned to conduct this study in order to understand the clinical profile in septic shock patients and to evaluate various in-hospital mortality predictors that could help in predicting the outcome due to septic shock even at the rural or peripheral hospitals.

Materials and Methods:

The present prospective observational study involving 145 patients with a diagnosis of septic shock as per SCCM/ACCP criteria (2016) was conducted at a tertiary care hospital from January 2020 to December 2020 following ethical approval with informed consent. Patients included were adult patients with septic shock admitted in department of medicine.

Patients who were excluded from study comprised of 1)Post traumatic cases of sepsis 2)Post operative cases of sepsis 3)Puerperal sepsis 4)Acute pancreatitis cases 5)Sepsis due to burn injury 6)Patients who died within 24 hours of admission and 7)Patients with COVID-19 pneumonia.

Detailed history was taken including demographic profile, co-morbidities and treatment history. Detailed clinical examination was done to assess the site of infection. Various routine serum haematological and biochemical parameters were evaluated at admission. These parameters included CHG, LFT, RFT, CRP and Lactate levels from blood gas. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and Platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) was determined by calculating ratio of absolute neutrophil count to absolute lymphocyte count and platelet count to absolute lymphocyte count respectively. Other investigations like ultrasound, CT, MRI, echocardiography and other radiological images were added according to relevance in each case.

To know about mortality predictors, various parameters were compared among survivors and non-survivors to assess the predictors for in-hospital mortality in septic shock. These parameters comprised of NLR, PLR, MPV, qCRP, Serum albumin levels, Serum total bilirubin levels and lactate levels at admission.

SPSS (Statistical Packages for Social Sciences) version 11.5 computer software was used for statistical analysis. Results obtained were expressed in proportions. For categorical variable statistical test chi-square was done and for continuous variable statistical test student t test was done. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

In our study, 145 patients who satisfied the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines were included. Majority (44.2%) of the patients were in the age group of 50-69 years. Males (55.2%) outnumbered females. Majority had rural background (59.31%). The majority (42.1%) of the patients had no known co-morbidity. 24.8% and 13.1% of the patients were known cases of diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease respectively as shown in Table 1.

| Table 1: Distribution of the Participants in Terms of co-morbidity (n = 145) |

|

Frequency |

Percentage |

None |

61 |

(42.1%) |

DM |

36 |

(24.8%) |

COPD |

19 |

(13.1%) |

HTN |

16 |

(11.0%) |

CKD |

14 |

(9.7%) |

CAD |

6 |

(4.1%) |

CLD |

3 |

(2.1%) |

HIV |

2 |

(1.4%) |

Chronic Viral Hepatitis |

2 |

(1.4%) |

Fever was the commonest (34.5%) mode of presentation of the patients in our study, followed by altered sensorium (29.7%) and shortness of breath (25.5%). Out of the 145 patients in our study who presented with septic shock, 69.7% patients survived whereas 30.3% patients did not survive. The highest mortality rate (41.9%) was seen in the age group of 60-69 years and only 58.1% patients survived in this age group of patients. The highest survival rate (87.5%) was seen in the age group of 18-29 years. The survival rate among male and female patients was 65% and 75.38% respectively.

Among the patients having pre-existent co-morbidities, the highest mortality was seen in the patients having chronic liver disease, chronic viral hepatitis and HIV positive patients with a mortality rate of 100% each, whereas the highest survival rate (56.25%) was seen among the patients who had only hypertension. It was observed that patients who were given primary care and stabilized in a primary or secondary health centre and then referred had a better survival (77.2%) as compared to directly visited the tertiary care centre in a sick state. It was observed that patients who had thrombocytopenia (platelet count <1,50,000/mm3), had significant more mortality (38 patients- 86.4%), as compared to those (6 patients- 13.6%) with a normal platelet count as shown in Table 2.

| Table 2: Association between Patient Status and Platelet Count (n = 145) |

Platelet Count |

Patient Status |

Chi-Squared Test |

Survivor |

Non-Survivor |

Total |

χ2 |

P Value |

<50000/mm3 |

1 (1.0%) |

15 (34.1%) |

16 (11.0%) |

39.130 |

<0.001 |

50000-100000/mm3 |

16 (15.8%) |

10 (22.7%) |

26 (17.9%) |

100000-150000/mm3 |

45 (44.6%) |

13 (29.5%) |

58 (40.0%) |

150000-400000/mm3 |

39 (38.6%) |

6 (13.6%) |

45 (31.0%) |

Total |

101 (100.0%) |

44 (100.0%) |

145 (100.0%) |

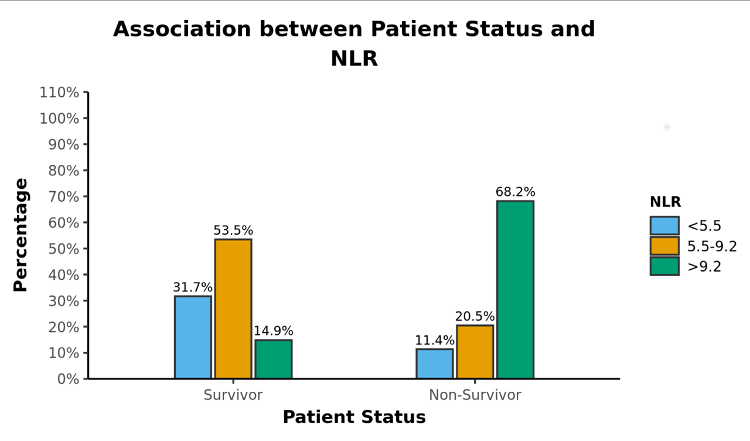

We found that patients who had hypoalbuminemia (serum albumin <3.5g/dl) had a higher mortality (35- patients, 78.6%) as compared to those (9 patients-21.4%) who had normal albumin levels. On observation of the NLR of the patients at admission, we found that out of the 45 patients who had an NLR >9.2, only 33% of them survived. Whereas, among the 37 patients having an NLR<5.5, 86.4% survived. 63 patients had an NLR value between 5.5 and 9.2, among which 85.71% patients survived as shown in Fig. 1.

|

Figure 1: Association between Patient Status and NLR at admission (n = 145) |

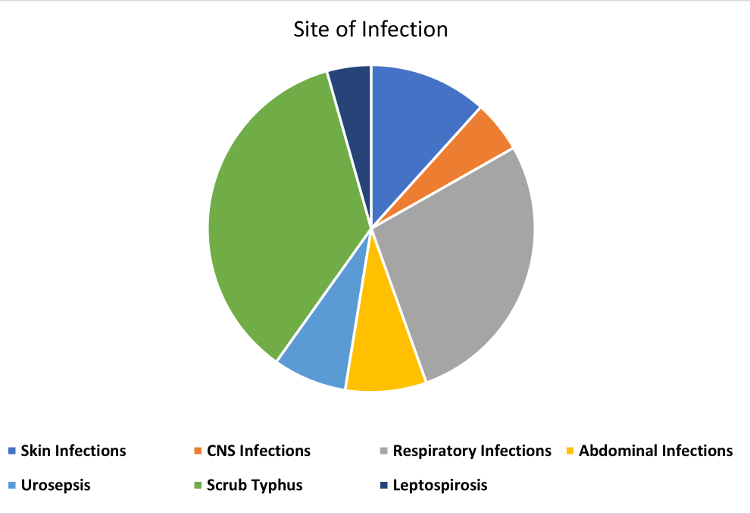

The patients, who had CRP levels of more than 50mg/dl, had a significantly higher mortality rate (40 patients- 90.9%) as compared to those who had qCRP levels less than 50mg/dl (4 patients-9.1%). In the present study, the maximum proportion (33.8%) of patients had scrub typhus, of which 81.63% survived. This was followed by patients having respiratory infections, of which 50% survived. Skin infections were present in 11% of the patients, of which 62.50% patients survived as shown in Fig. 2.

|

Figure 2: Association between Patient Status and Site of Infection (n = 145) |

Among the various diagnosis of infection, the worst mortality rate was among the group of patients who had respiratory infections, in which 50% patients did not survive. The best survival rate was seen in patients having urosepsis, among which 90% patients survived. In this study, the mortality rates among patients requiring vasopressor therapy for different durations varied significantly with mortality rates of 46.8% and 37% in patients requiring vasopressor therapy for less than 2 hours and more than 24 hours respectively as shown in Table 3.

| Table 3: Association Between Patient Status and duration of vasopressor support (n = 145) |

Duration of Vasopressor support |

Survived |

Didn't survive |

No. of patients |

% |

< 2 hours |

17 (16.83%) |

15 (34.09%) |

32 |

15.17 |

2-12 hours |

14 (13.86%) |

1 (2.27%) |

15 |

10.34 |

12-24 hours |

36 (35.64%) |

8 (18.48%) |

44 |

30.34 |

>24 hours |

34 (33.66%) |

20 (45.45%) |

54 |

37.24 |

Total |

101 |

44 |

145 |

100 |

Discussion

Although the study was limited to evaluation of only 145 patients, it reflects a strikingly higher mortality rate among septic shock patients in a tertiary care hospital, corroborative with other studies done previously.[6-8] Another finding of this study was the scrub typhus as the most common source of infection in this hilly region leading to septic shock as it is endemic in this region. Male gender showed predominance over females for developing infectious complications as was observed in other previous studies.[7,9,10]

Majority patients were without any co-morbidity, though among various co-morbidities which were found among patients, Diabetes was the most common leading to septic shock followed by COPD similar to the study performed by Merin Babu et al,[7] in which diabetes(51.2%) was the most common co-morbidity found.

Patients who received initial treatment in primary or secondary health care centers had better survival than those who presented in tertiary care hospital directly in sick state as early diagnosis and antibiotic administration in sepsis and septic shock provides morbidity as well as mortality benefit. This was in accordance with the mortality rates observed in the study done by Nicholas M. Mohr,[11] who also observed a 5.6% increase in mortality among the patients who bypassed the rural hospitals.

Patients who had thrombocytopenia, hypoalbuminemia and raised total bilirubin levels had a significantly higher mortality as compared to those with a normal platelet count or normal albumin and bilirubin levels, corroborative with various previous studies.[12-14]

High NLR was significantly associated with mortality similar to the observations made by Rakesh Kumar Mandal et al,[15] who concluded that NLR was independently associated with poor clinical prognosis in sepsis and septic shock and a high NLR >10 was significantly associated with in hospital mortality.

High levels of CRP, lactate levels and mean platelet volume also showed strong positive correlation with mortality.[16-18] All these are the markers of inflammation and as the severity of sepsis increases the change in these parameters can predict the outcome. PLR value had no correlation with mortality.

In our study, patients who required vasopressor for duration less than 2 hours were those with various co-morbidities and severe sepsis who could not survive for longer duration despite on inotropic support. Though, in a study performed by Vikas Kumar et al,[19] no statistically significant correlation was observed between mortality and duration of vasopressor use when compared for before and after 48 hours.

Conclusions

Our study was done to study the various clinical presentations of septic shock patients and identifying the key mortality predictors among such patients, so that the results can help the physicians in early diagnosis, prompt initiation of treatment and interpretation of the various laboratory parameters. The clinical profile of septic shock patients in our setup is different as compared to western countries due to high prevalence of tropical infections especially Scrub typhus in our study. We found a strong positive correlation of Thrombocytopenia and Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) with mortality in septic shock patients as compared to other parameters studied. Therefore, we propose that these simple hematological parameters may be routinely used especially in resource limited settings like ours and health care centers without proper laboratory facilities to assess the severity of disease, prognosis and plan for referral to higher centers at appropriate time in patients with septic shock.

Study Limitations

This was a small observational study with only 145 patients. We included only simple lab parameters and no follow up after discharge was done. Bigger studies with easily available parameters and follow up for early post discharge complications will guide us in better management of these patients.

References

- Hotchkiss RS, Moldawer LL, Opal SM, Reinhart K, Turnbull IR, Vincent J-L. Sepsis and septic shock. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016 Jun 30;2:16045.

- Shankar-Hari M, Phillips GS, Levy ML, Seymour CW, Liu VX, Deutschman CS, et al. Developing a New Definition and Assessing New Clinical Criteria for Septic Shock: For the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016 Feb 23;315(8):775-87.

- Ferrario M, Cambiaghi A, Brunelli L, Giordano S, Caironi P, Guatteri L, et al. Mortality prediction in patients with severe septic shock: a pilot study using a target metabolomics approach. Sci Rep. 2016 Feb 5;6:20391.

- Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992 Jun;101(6):1644-55.

- Shen Y, Huang X, Zhang W. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic predictor of mortality for sepsis: interaction effect with disease severity-a retrospective study. BMJ Open. 2019 Jan 25;9(1):e022896.

- Paary TT, Kalaiselvan MS, Renuka MK, Arunkumar AS. Clinical profile and outcome of patients with severe sepsis treated in an intensive care unit in India. Ceylon Med J. 2016 Dec 30;61(4):181-4.

- Babu M, Menon VP, Uma Devi P. Epidemiology and outcome among severe sepsis and septic shock patients in a south Indian tertiary care hospital. International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences.2017 May 1;256-9.

- Dash L, Singh LK, Murmu M, P SK, Kerketta A, Hiregoudar MB. Clinical profile and outcome of organ dysfunction in sepsis. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 2018 May 25;6(6):1927-33.

- Angele MK, Pratschke S, Hubbard WJ, Chaudry IH. Gender differences in sepsis. Virulence. 2014 Jan 1;5(1):12-9.

- Naqash H, Shah PA. Clinical profile of septic shock patients in a tertiary care hospital. International Journal of Current Advanced Research. 2017 Dec;06(12):8145-8147.

- Mohr NM, Harland KK, Shane DM, Ahmed A, Fuller BM, Ward MM, et al. Rural Patients with Severe Sepsis or Septic Shock Who Bypass Rural Hospitals Have Increased Mortality: An Instrumental Variables Approach. Crit Care Med. 2017 Jan;45(1):85-93.

- Venkata C, Kashyap R, Farmer JC, Afessa B. Thrombocytopenia in adult patients with sepsis: incidence, risk factors, and its association with clinical outcome. J Intensive Care. 2013;1(1):9.

- Gupta L, James BS. 727: Hypoalbunaemia as a prognostic factor for sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock. Critical Care Medicine. 2012 Dec;40(12):1-328.

- Patel JJ, Taneja A, Niccum D, Kumar G, Jacobs E, Nanchal R. The association of serum bilirubin levels on the outcomes of severe sepsis. J Intensive Care Med. 2015 Jan;30(1):23-9.

- Mandal RK, Valenzuela PB. Neutrophil-Lymphocyte count ratio on admission as a predictor of Bacteremia and In Hospital Mortality among Sepsis and Septic shock In Patients at Rizal Medical Center. Asian J Med Sci. 2018 May 1;9(3):36-40.

- Ryoo SM, Han KS, Ahn S, Shin TG, Hwang SY, Chung SP, et al. The usefulness of C reactive protein and procalcitonin to predict prognosis in septic shock patients: A multicenter prospective registry-based observational study. Sci Rep. 2019 Apr 29;9(1):6579.

- Kim CH, Kim SJ, Lee MJ, Kwon YE, Kim YL, Park KS, et al. An increase in mean platelet volume from baseline is associated with mortality in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. PLoS One. 2015 Jan 1;10(3):e0119437.

- Lee SM, An WS. New clinical criteria for septic shock: serum lactate level as new emerging vital sign. J Thorac Dis. 2016 Jul;8(7):1388-90.

- Kumar V, Srinivas S, Le T-H, Barnes M, Kumar S, Redinski J. Effects of Length of Vasopressors Infusion on Mortality. Cureus. 2019 Aug 7;11(8):e5336.

|